It was from Busan that Joseon Tongsinsa, the Korean missions to Japan launched in the early 17th century in the wake of Japanese Invasions, departed to promote peaceful bilateral relations. The history of Busan as an active hub of international exchange continues to this day.

The first port to be opened in the Joseon period under the Korea-Japan Treaty of Amity, or the Ganghwa Treaty of 1876, Busan is now the world’s sixth-largest port in terms of total cargo volume. Busan Harbor Bridge, completed in 2014, stretches 3,368 meters across the port area.© Busan Metropolitan City (Photographer Jeong Eul-ho)

Busan Port is Korea’s biggest gateway for imports and exports and consequently has major influence on both the local and national economy. At the frontier of the Eurasian continent, facing Japan across the Korea Strait, it has tremendous potential as East Asia’s logistics and distribution hub.Busan handles more than 60 percent of Korea’s import and export cargo. According to the Busan Port Authority, Busan handled 21,663,000 TEU in 2018, taking sixth place in the world in terms of total cargo volume for two consecutive years.

The city’s history of international exchange through maritime routes dates back to ancient times. Dadaepo, a small coastal town in today’s Busan, is referred to in the eighth-century source “The Chronicles of Japan” (Nihon Shoki) as “Tadairagen” or “Tatara,” suggesting that it already played a central role in Korea-Japan trade and cultural exchange at the beginning of the historic period. Tatara also refers to the traditional Japanese furnace used for smelting iron and steel, so it is associated with the introduction of iron-working technology.

Northeast Asian Trade Center

Located along the side streets across from the city’s main train station, Busan's Chinatown originated in 1884. A popular tourist attraction, it has an interesting series of murals based on the characters and stories from “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” (Sanguo yanyi). Many ethnic Chinese live in the area.© Ahn Hong-beom

“Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms” (Samguk yusa), a 13th-century collection of legends and historical accounts, depicts the Busan area as a place of seaborne international exchange early on in history. Legend has it that in the area close to today’s Busan, King Suro, founder of Geumgwan Gaya (Gold Crown Gaya, 43–532), welcomed Heo Hwang-ok, believed to be a princess of an Indian kingdom called “Ayuta,” to be his wife. The story of Queen Heo is generally accepted as historical fact today. Historians propose the twin-fish pattern painted on the gate to the graveyard of King Suro in Gimhae as evidence of the queen’s Indian origin, on the basis of its iconographic association with the Indian civilization.

As proved by the number of Gaya sites and relics excavated in the Busan and South Gyeongsang area, Gaya’s overseas relations were not limited to India, however. After the disintegration of the Former Gaya Confederacy in the early fifth century, a large number of Gaya people migrated to Japan. They introduced skills for making ironware and unglazed pottery, called sueki, contributing to the development of ancient Japanese civilization.

As its geographical name Gimhae (literally, “Sea of Iron”) denotes, the heartland of the Former Gaya Confederacy abounded in iron ore. The Gaya states located along the beautiful shores of the South Sea and the Nakdong River emerged as a major center of Northeast Asian trade, thanks to their rich iron ore reserves. As the Northeast Asian community diversified after the collapse of the Chinese Han Dynasty, Gaya gained significance as a stopover connecting the Japanese archipelago and the Chinese continent. Located along a major trade route where seaways from different Asian countries intersected, Gaya provided iron to neighboring countries.

“The Chronicles of Japan” records that in the mid-fourth century, King Geunchogo of Baekje sent an assortment of goods to Japan, which included 40 iron nuggets. Made by striking iron ore into thin bars, iron nuggets were an important base material for manufacturing diverse kinds of ironware. Similar iron pieces have been found in Baekje and Silla tombs as well as ancient tombs across Japan. Specifically, the dozens of iron bars excavated in the old Gaya regions indicate that they were not only used as burial objects but also as currency and ironware materials.

Busan’s Chinatown was formed when the Qing Dynasty opened a consulate here in 1884. It remains to this day across the street from Busan Station. The roads here are lined with Chinese restaurants, groceries, currency exchange counters and other businesses run by Chinese Koreans, as well as schools for their children.

Chinatown and Japanese Quarters

“Texas Street” at the entrance of Chinatown is lined with souvenir shops and nightclubs for foreign sailors. When ocean freighters come to port, the street is crowded with seafaring men. © Ahn Hong-beom

Korea’s southernmost Chinatown was created by Chinese people who arrived in the 17th to 18th century during the late Joseon period, in order to work on the reclamation of Busan Port and the construction of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service. Its current residents are their third- and fourth-generation descendants. In the early days, Chinese residents received support from their home country to settle down in Busan. A large portion of the ethnic Chinese population in Busan moved here after the Korean War.

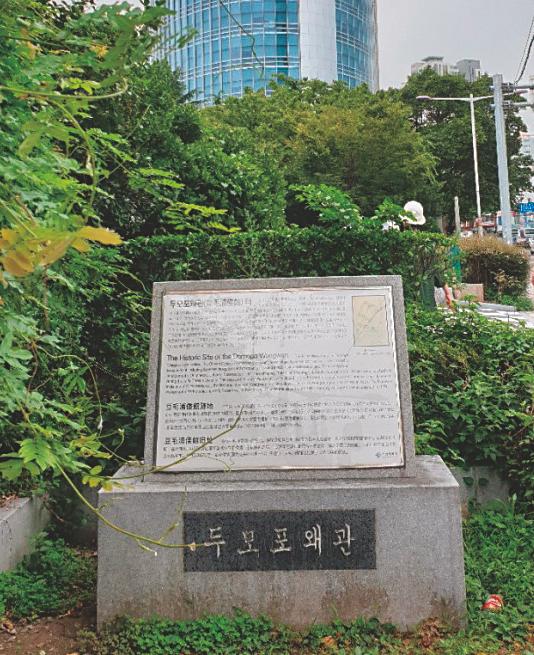

In 1953, the Chinatown went through a major change when Busan Station was destroyed by a great fire and the adjacent brothels moved into this area. They eventually were forced out, however, when Korea and China established diplomatic relations in 1992 and Busan and Shanghai became sister cities the next year. In celebration of this special relationship, the district was named “Shanghai Street,” and since 2004, the Busan Chinatown Culture Festival has been held here.In the Joseon era, Busan also had Japanese quarters, calledwaegwan. The Joseon government built these quarters at open ports for the Japanese to live in and engage in trade and diplomatic exchanges, as well as to help drive off Japanese pirates who had infested coastal areas since the 14th century, toward the end of the Goryeo period. Waegwan were built at three ports: Busanpo and Jepo in Jinhae in 1407, and then at Yeompo in Ulsan in 1426. Together, they were called the “Three Waegwan Ports” (Sampo Waegwan). In 1544, however, the Japanese quarters were dismantled, except that in Busan, after incidents of plunder in Tongyeong committed by Japanese people.

Diplomatic relations between Joseon and Japan, severed after Japan’s two invasions in 1592 and 1597, were restored under the “good neighborly diplomacy” of Tokugawa Ieyasu, the first shogun of the Edo Bakufu. Subsequently, Japanese quarters were rebuilt in a few places along the southeastern coast, with the one in Busan accommodating some 500 Japanese men. Another one in Choryang, built in the late 17th century, covered 100,000 pyeong (approximately 82 acres) with individual homes, accommodations for visiting envoys and trade facilities. The buildings were provided by the Joseon government, but the interiors were decorated in Japanese style with tatami floors. Although the perimeters had checkpoints that prevented residents from freely leaving, they were allowed to create a little Japanese community inside Korean territory, walking around in their traditional clothing with a Japanese sword slung from the waist.

Base for Cultural Exchange

A stone marker showing that a waegwan, or Japanese quarters, was located in Dumopo. Built in 1607, the Japanese quarters in Dumopo lasted for over 70 years before it was closed and a new one built at Choryang. © Naver blog “Outing on a Lovely Day”

Since ancient times, there had been repeated armed conflicts between Korea and Japan. However, during the 210 years of the Edo period, which corresponds with late Joseon in Korea, the two countries enjoyed peaceful relations mediated by Joseon emissaries to Japan. Following the restoration of bilateral relations in 1607, Joseon dispatched large-scale diplomatic missions to Japan on 12 occasions. Such systematic exchange to promote peace and cultural understanding between two neighboring countries is rarely found in the history of the world.

In 2014, two non-governmental organizations — the Busan Cultural Foundation and Japan’s Liaison Council of All Places Associated with Chosen Tsushinshi — embarked on joint efforts to compile the “Documents on Joseon Tongsinsa/Chosen Tsushinshi: The History of Peace Building and Cultural Exchange between Korea and Japan from the 17th to 19th century,” which was inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2017. Consisting of 63 documents and records (124 items) from Korea and 48 documents and records (209 items) from Japan, the body of materials is especially significant as the first documentary heritage of Busan to be included in the UNESCO archive. It is also the first UNESCO recognition gained jointly by Korea and Japan, made possible through the collaboration of civic groups from both countries.

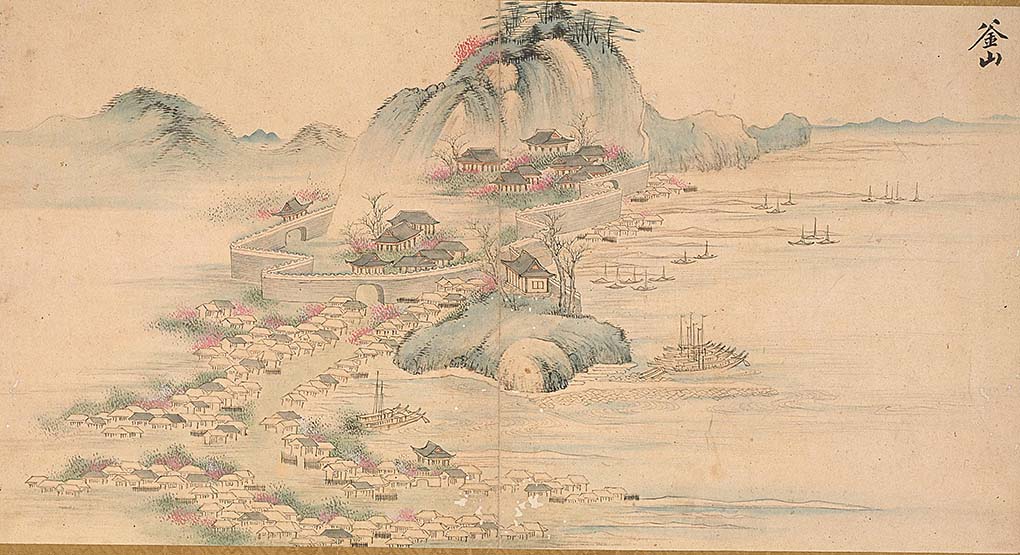

Each mission to Japan usually consisted of some 400 to 500 members, including envoys, assistants, scribes, military officers and musicians, among others. After leaving Seoul, the procession arrived at Busan and stayed there for a while to prepare for diplomatic activities and wait for the right time for the sea journey. They had to be mindful of weather and wind conditions as the Korea Strait was often hard to navigate. When good days for sailing came, they held sacrificial rites for the sea gods at Yeonggadae pavilion and departed from the nearby dock in six ships.

Peacemaking Missions

Entering Japan at Tsushima Island, they continued their journey to Edo (modern-day Tokyo) passing through 53 stations. To welcome the Korean missions, Japan shouldered huge expenses, mobilizing 338,500 workers and 77,645 horses in the case of the eighth mission in 1711 — a procession of immense scale even by today’s standards.

This was before Japan opened its doors to the West, maintaining a policy of seclusion. The Japanese regarded the visit of the Korean envoys as an occasion for celebration and welcomed them with grand events. The missions received great attention not only from government officials but people from all walks of life, including soldiers, commoners, merchants and farmers.

The Japanese people considered it an honor to meet Korean writers and artists, so they would visit their lodgings to exchange poems, critiques, writings, paintings and calligraphic works. Members of the delegation were kept so busy responding to such requests that it was hard for some to find time to sleep. Documents and paintings describing those scenes remain in both Korea and Japan. Japanese artists of the Edo period were quite keen to adopt Joseon’s culture, and these interactions are considered to have propelled the development of Japan’s arts and culture during the period.

Over one hundred books recording the exchanges were published in Japan. Joseon writers and officials also produced numerous reports after their return. These served as valuable literature aiding mutual understanding between the two countries.

After leaving Seoul, the procession arrived at Busan and stayed there for a while to prepare for diplomatic activities and wait for the right time for the sea journey.

“Busan” from the “Sea Route of Scenic Beauty” (Saro seunggu do) by Yi Seong-rin (1718–1777). 1748. Ink and light color on paper. 35.2 x 70.3 cm.Yi Seong-rin, an artist with the Royal Bureau of Painting (Dohwaseo), zepicted the long trip that the Joseon emissaries took from Busan to Edo, Japan. Consisting of 30 scenes, it is the only painting remaining in Korea documenting the journey of the Joseon mission of 1748. © National Museum of Korea

Bridging Human Distance

Alok Kumar Roy Professor, Busan University of Foreign Studies

Busan buzzed with activities on November 25–26, 2019, as it once again hosted the Commemorative Summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and the Republic of Korea. The gathering marked the 30th anniversary of ASEAN-Korean relations and set the stage for the First Mekong-ROK Summit the following day. The talks on fostering peace and prosperity were a reminder that dialogue among heads of state also augments cultural diplomacy, where “one plus one” equals more than two.

“ASEAN Crafts: From Heritage to the Contemporary,” a special exhibition marking the 30th anniversary of dialogue relations between South Korea and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, attracts visitors at the ASEAN Culture House in Busan. The exhibition will continue until January 15, 2020.

Private Sector Interactions

In Busan today, the ASEAN Culture House (ACH) is emblematic of the city’s people-to-people spirit, sparking the imagination and interest in the cultures of places that once seemed remote. From introducing traditional garments and cuisines of Southeast Asian countries to offering language and cultural courses, the ACH’s diverse programs initiate meaningful and vibrant dialogues promoting cultural and diplomatic ties from the grassroots level. The ACH’s involvement with academic and professional institutions among the 10-member ASEAN has significantly strengthened interactions in the private sector.

The integration of demographic diversity is another task of Busan as a global city. Today, some 65,000 immigrants contribute their skills and talents to Busan, of which around 12,000 are international students. Among them, the ASEAN population forms one of the largest communities. Functionally incorporating them into Busan becomes easier when Korean citizens are actively involved, and the ACH takes a lead role in engaging foreign residents and students in efforts for mutually beneficial togetherness.

The pursuit of urban diplomacy is a major focus for any global city. The Busan Metropolitan City and the Busan Foundation for International Cooperation (BFIC) endeavor to fulfill this task with a global mindset, building bridges and connecting geographies through human networks. Today, their activities transcend links with partner cities, expanding to new areas to strengthen cooperation with people throughout the world.

In recent years, Busan’s global visibility has remarkably grown through its capacity-building training programs. In 2019, the Colombo Plan Staff College (CPSC) sent a 20-member delegation from Nepal, consisting of medical and technical professionals, to explore human resources development in polytechnic and healthcare education. In 2020, CPSC plans to do the same in finance and banking. In 2019 alone, Busan facilitated training in the fields of smart farming, ocean and fisheries development, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (exclusively for Laos) and road safety (exclusively for Ecuador).

Global Visibility

For the last four years, Busan has steered the Citizen’s Eurasia Expedition to raise awareness about the city’s economic potential and cultural affinity to the Eurasian continent. The 2019 journey, which took them to 10 cities in five countries, including China, Mongolia, Russia, Poland and Germany, had two additional missions: retrace the history of Korea’s March First Independence Movement on the occasion of its 100th anniversary, and learn about the complex task of Korean unification from the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

At the same time, the BFIC-operated Global Center supports immigrants and expatriate residents by providing information, translation services (in 13 languages) and professional consultations regarding issues including laws, immigration, labor, international marriage and family relations, taxation, and others.

At a tumultuous time when globalization is often seen as a challenge, the experience of Busan offers a fresh perspective. Busan has, in many ways, reshaped our sense of the “distance” between countries and cultures, serving as a testament to open-mindedness and innovative planning that can bridge the separation.

Park Hwa-jinProfessor, Pukyong National University