A lack of research materials on the Baekje Kingdom had left its culturelargely unknown before the discovery of a king’s tomb began to reveal itsessence. Found by accident in 1971 in the process of building a drainagesystem in a Baekje royal graveyard in Songsan-ri, in its old capitalGongju, the tomb of King Muryeong is the only royal sepulcher from thethree Kingdoms period (57 B.c.-A.D. 668) with identifi ed occupants.

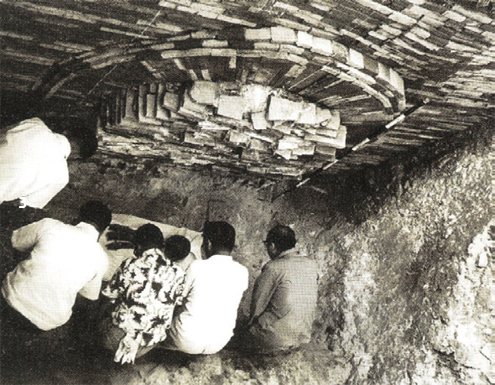

The main chamber of the tomb of KingMuryeong, viewed from the passageway.The tomb was found in 1971 in aBaekje royal graveyard in Songsanri,Gongju. Under the vault, built bystacking up bricks of different shapesand patterns, the rectangular chambercontained the wooden coffins of theBaekje king and his wife, which had collapsedunder the weight of time.

Located in the East Asian Monsoon region, the Korean peninsula entered into yet another rainyseason in the summer of 1971. A rainy spell often means disaster at a cultural heritage site, butthat year in Gongju, it was a blessing in disguise.

Along with Silla and Goguryeo, the Baekje Kingdom, which lasted for almost 700 years from its foundationin 18 B.C., was one of the Three Kingdoms which prospered in ancient Korea. In Gongju, the secondcapital of Baekje, located in current South Chungcheong Province, there is a cluster of royal tombsin Songsan-ri, at the southern foot of a low hill, with the Geum River flowing through the city from thenorth. At this historic site, where the soft contours of ancient burial mounds create a cozy atmosphere,the discovery of the tomb of Baekje’s 25th monarch, King Muryeong (r. 501–523), and his wife cameabout serendipitously through rainfall.

Drainage System Maintenance for Rainy Season

The 16th-century book “Revised and Augmented Survey of the Geography of Korea" (Sinjeung donggukyeoji seungnam) has an entry on Gongju describing the royal tombs in Songsan-ri: “There is a countyschool 3 li to the west of the town, with a cluster of old tombs to its west. They are said to be royaltombs from Baekje but the exact occupants are unknown.” The tombs had already been noted in theJoseon era as belonging to Baekje kings. Later, in the early half of the 20th century, excavations revealedthat the site was a royal cemetery created during 475–538 when Ungjin (present-day Gongju) wasthe kingdom’s capital, although the owner of each grave was not clarified. In the early 1970s, with sixmounds of presumed royal tombs exposed, the area was registered as a state-designated historic site.

Every summer, the ancient tombs suffered damage from downpours because rainwater flowingdown from the back hill would seep into the underground burial chambers. To protect the two mounds(No. 5 and No. 6) lying next to each other in an east-west direction, the Office of Cultural Properties (thecurrent Cultural Heritage Administration) under the Ministry of Culture and Information decided to diga drainage channel running parallel with them, about three meters away toward the back hill. Workbegan on June 29, when the monsoonal front started to move northward toward Korea’s southern coast,with the aim of finishing it before the rain began.

A week later, at around 2 p.m. on July 5, one of the workers digging the channel hit a river rock withhis spade. “A river rock down in the ground? I knew instantly something was strange, because riverrocks were used for tombs. Digging deeper, I came to a solid brick structure, and the dirt that turned upcontained lime. Eventually, my pickax clanged on something hard — traditional bricks,” said Kim Yeongil,then site manager from the contractor Samnam Construction. This moment heralded the unexpecteddiscovery of a magnificent royal tomb and a landmark event in the history of Korean archaeology. Thepickax had touched on the ceiling for the southern part of the passageway to the main chamber, builtentirely of traditional bricks.

At this point, no one knew who was interred in the tomb although the brickwork and layout, whichclosely resembled Tomb No. 6 directly in front of it, led those on site to believe it was an untouched royalburial chamber.

A Nightlong Downpour

What were they supposed to do with the newly discovered brick tomb? The site manager immediatelyreported the discovery to Kim Yeong-bae, director of the Gongju branch of the National Museumof Korea (the current Gongju National Museum). The museum was obliged to report it to the Office ofCultural Properties to obtain permission for excavation, but under the excitement of finding a new royaltomb from Baekje, the proper procedures were ignored. On the same day, museum officials rushedto start digging up the site with some local archaeologists, and became convinced that it was indeed aBaekje royal tomb built with traditional bricks.

Found in the tomb of King Muryeong, the ornaments for the king’scrown, cut out in honeysuckle design from pure gold plate, resembleflames of fire. Length: 30.7cm. Width: 14cm. National TreasureNo. 154. Gongju National Museum.

the discovery of King Muryeong’s tomb brought Baekje’s history out of obscurity.Baekje had remained a dark corner in ancient Korean history due to a shortage of relevant literature,but the relics from the tomb provided solid evidence that shed light onthe ancient kingdom’s history from diverse perspectives.

The ornaments for the queen’s crown were found at the head partof her coffin. Length: 22.2cm. Width: 13.4cm. National Treasure No.155. National Museum of Korea.

The Office of Cultural Properties was informed of the discovery the next day, July 6, by the Gongjumunicipal government. The office sent staff to the site to investigate the situation, ordered an immediatehalt to any unauthorized digging, and decided to organize a formal excavation team. On July 7, the team arrived. It was led by Kim Won-ryong, the thendirector of the National Museum of Korea, and includedresearchers from the Cultural Properties ResearchInstitute affiliated to the Office of Cultural Properties,such as Cho Yu-jeon and Ji Gon-gil (see box). The excavationbegan at 4 p.m. on the same day.

After just two hours, however, a sudden torrent ofrain came down. The site was flooded and rainwaterthreatened to leak into the royal burial chamber. Theteam was compelled to abandon the site, leaving onlythe construction crew, who struggled through the pitchblacknight to dig a drainage ditch. In the meantime,the excavation team gathered at a motel in downtownGongju to discuss how to proceed with the excavation,and decided to resume work the next day.

The Excavation Site Buzzes with Excitement

The sky cleared the next day and the sun shonebrightly. Having resumed the excavation at 5 a.m. onJuly 8, the team successfully uncovered the entranceof the passageway leading to the main chamber. Clearly,it was another Baekje royal tomb. At 4 p.m., beforethe tomb was finally opened, a simple memorial ritewas held for its occupants, with three dried pollacksand rice wine placed on a small table. At last, the teamstarted to remove the bricks blocking the entrance oneby one. When the dark passageway was unsealed forthe first time in 1,500 years, a cool draught blew fromthe inside like a whiff of white vapor or cool air comingfrom a car’s air conditioner in midsummer.

The excavation team conducts a simple memorial rite before removingbricks blocking the tomb of King Muryeong on July 8, 1971.

LESSONSLEARNED

FROM A

MISGUIDED

EXCAVATION

“It might sound like an excuse, but I have to comfort myself with thethought that such was the level of Korean archaeology at the time. However,I’m grateful for the painful lessons we learned from that mistake. All followingarchaeological projects were carried out more carefully, based on meticulousplans.”

Ji Gon-gil, former director of the National Museum of Korea, refers to the1970s when he worked in Gyeongju, the old capital of Silla, as the pinnacle ofhis archaeological career. Fondly, he keeps looking back to the time when heunearthed the two royal tombs — the Tomb of the Heavenly Horse (Cheonmachong)and the Great Tomb of Hwangnam (Hwangnam Daechong) —from 1973 to 1976. While it was an honor for him to work on those projects, Jisays, the excavation of King Muryeong’s tomb remains a source of irrevocableshame.

Currently serving as chairman of the Overseas Korean Cultural HeritageFoundation, Ji graduated from Seoul National University with a majorin archaeology and anthropology, before entering officialdom in November1968 as a researcher at the Office of Cultural Properties (predecessor of theCultural Heritage Administration). On July 7, 1971, he was abruptly orderedto go to Gongju with a few of his colleagues. Before he got there, he had noidea that an ancient tomb, presumably of Baekje royalty, had been discovered,and that he would be responsible for investigating it. “None of us headingfor Gongju knew anything about it,” he recalls. “Upon our arrival, we werestunned at the sight of an ancient brick tomb with its front slightly exposed.”

Although he was just a young researcher who was not in a position tomake decisions, he has been tormented by the fact that he took a leading rolein a project recorded in archaeological history as a ludicrously slapdash excavation.“The tomb of King Muryeong was excavated in a chaotic and carelessmanner, with the entire process from the discovery to the actual excavationexposed in real time to the media and the local community. In the uproar andexcitement, our team found it hard to keep cool and rational,” he recalls.

In fact, there’s another thing that Ji regrets about the excavation. At thetime, one of his duties was to take photos, the primary evidence for the originalcondition of the site, with all the relics in their right positions. However, heproduced few good photographic materials, and most of the scanty numberof photos available were taken by reporters on the site. What happened?

“Inside the tomb, I worked hard photographing the chamber. It was onlyafter I developed my films back at the Seoul office that I realized somethingwas wrong with the photos. I had taken a brand new camera to the site, so Iwas clumsy with handling it. Some of the shots were exposed on one-half ofthe frame, and only a few cuts could be saved,” he explains.

Gilt-bronze shoes found at the feetpart inside the king’s coffi n. Length:35cm. Gongju National Museum.

As an opening large enough for human access wassecured, Kim Won-ryong and Kim Yeong-bae went intothe tomb holding an incandescent lantern. The passagewaywas a bleak tunnel, the ceiling a bit lower thanthe height of an average man. The roots of acacia treeshanging down from the arched ceiling made it look likea haunted place. Halfway along, they ran into a fierce-looking stone animal resembling a boar with ahorn on its forehead, seemingly there to protect the tomb and ward off evil spirits from outside.

At the end of the passageway was a rectangular chamber with a vaulted ceiling. It was not very large,and the floor was strewn with what in the gloom looked like dingy planks of wood.

They turned out tobe wooden coffins that had collapsed under the weight of time. Golden relics peeked through the gaps.The two archaeologists could hardly believe their eyes, their intuition telling them that it had never beentouched by human hands since the burial. “Discovering an undamaged tomb from Baekje! A royal tombat that!” They could not contain their excitement.

Who is Buried in the tomb?

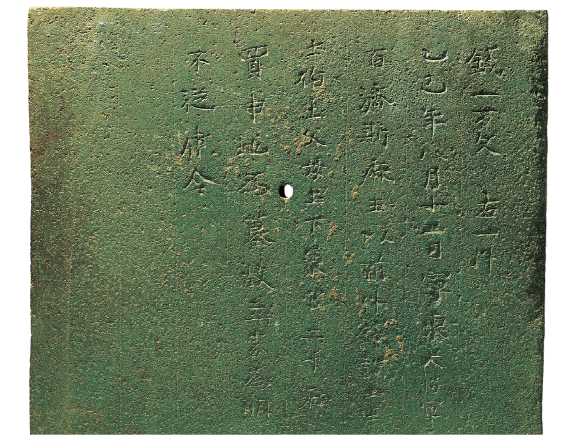

One of the two stone slabs foundhalfway along the tomb’s passagewayis engraved with the statement thatthe land for the tomb was purchasedfrom the gods of heaven and earth,along with the name of the occupant,date of death, and date of burial.Width: 41.5cm. Length: 35cm. Thickness:5cm. National Treasure No.163. Gongju National Museum.

Their euphoria reached a climax on their way out when they found two stone slabs in front of themenacing stone animal halfway along the passage. The lantern light revealed characters carved in classicalChinese which were interpreted to mean “King Sama of Baekje, the great general who broughtpeace to the east.” Sama was a title conferred on King Muryeong of Baekje by the emperor of the LiangDynasty (502–557), one of the southern dynasties of China. Kim Won-ryong recollects the moment: “Iwas so stunned that I was beside myself.”

Kim Won-ryong’s extreme excitement at finding out the identity of the tomb’s occupant impaired hisjudgment, and he ended up allowing the excavation to be conducted in an unprecedentedly haphazardmanner. An experienced archaeologist should have calmed himself down,brought all work to a halt, and invested time in devising a detailed actionplan. Kim, however, opted for an immediate excavation. Further cloudinghis judgment was the chaotic atmosphere, with a large crowd of reportersfrom all over the country waiting anxiously outside the tomb to reportthe historic discovery.

Thus, the tomb of King Muryeong was unearthedas soon as its occupant was identified, and the chamber was completelyemptied by 8 a.m. the next day, July 9. Nobody had documented what hadbeen found where, and in what condition.

With neither a plan nor proper protocol, King Muryeong’s tomb wasexcavated in such haste that it could have been the work of grave robbers.Ever since, the project has been repeatedly criticized and bemoaned by the Korean archaeological community. Nevertheless, the unfortunate manner of the excavationhas not overshadowed its results. Of the 114 kings of the Three Kingdoms and the subsequentUnified Silla periods — 31 from Baekje, 27 from Goguryeo and 56 from Silla, which unifiedthe three kingdoms — only King Muryeong has had his tomb identified by posterity.

Baekje’s History Salvaged from Obscurity

A stone guardian animal found alongthe passageway. Length: 47cm.Height: 30cm. Width: 22cm. NationalTreasure No. 162. Gongju NationalMuseum.

In addition, discovery of his tomb brought Baekje’s history out of obscurity. Baekje hadremained a dark corner in ancient Korean history due to a shortage of relevant literature, butthe relics from the tomb provided solid evidence that shed light on the ancient kingdom’s historyfrom diverse perspectives. Specifically the two stone slabs, engraved with the statementthat the king and the queen had been buried in land purchased from the gods of heaven and earth,offered a glimpse of the solemn funeral customs observed by the people of Baekje.

The tomb of King Muryeong and his wife yielded a splendid array of artifacts — over 3,000 items ofabout 100 kinds. It was evident that some of the articles had been imported from China. Moreover, thewooden coffins for the royal couple were made of Japanese umbrella pine, whose only natural habitat isknown to be the Japanese archipelago. These observations demonstrate that Baekje carried out culturaland material exchange with neighboring nations by means of maritime trade, and that the royal familymaintained close relations with Japan.

Visitors to the Gongju NationalMuseum look around the exhibits,including the wooden coffi ns for theroyal couple and the guardian animal,restored almost to their originalstate.