Ulleungdo is one of nature’s most unique treasure troves. It is home to a potpourri of flora that has adapted and evolved over millions of years into new and unmatched species.

The Ulleungdo raspberry, commonly found in the island’s mountainous regions, has larger leaves and flowers than the mainland Korean raspberry. The beautifully detailed botanical illustrations featured in this article are the work of members of the Botanical Artists Society of Korea. Founded in 2007, the society promotes the beauty of botanical art through regular exhibitions, open competitions, joint exhibitions with overseas institutions, and publications.

© Ye Sook Kim

Ulleungdo boasts vegetation not found anywhere else in the world. It is currently home to around five hundred species of vascular plants — trees, flowering plants, grasses, and shrubs that have their own systems to transport water and nutrients internally.

About fifty of these plants are endemic to the island. They have undergone a long evolutionary process since Ulleungdo’s formation approximately 2.5 million years ago. Some are similar to mainland species but have traits that set them apart. Many others are completely distinct from progenitor species on the mainland, shaped by the island’s topographical and geological characteristics.

Ulleungdo is not part of a larger landmass that became detached through tectonic shifts or rising sea levels. Rather, the island, situated some 140 kilometers from mainland Korea, rose from volcanic eruptions at the bottom of the ocean. Its local plant life has thus undergone a separate process of evolution during the current geological period — the Cenozoic Era. This is why Korean botanists classify Ulleungdo as a self-contained floral zone. Other such zones include the northern, central, and southern parts of the Korean peninsula, and Jejudo. Although both are volcanic islands, Ulleungdo’s flora is distinct from that of Jejudo.

ADAPTED FOR SURVIVAL

In its formative period, Ulleungdo’s environment was not conducive to sustaining life; its hot, barren land lacked soil, and water and nutrients were scarce. This prompts far-reaching questions: From where did the seeds of the endemic plants populating the island originate? Are the pioneer species that colonized Ulleungdo from the same lineage or were multiple lineages involved in speciation? How much speciation has occurred within populations?

In the beginning, moss and lichen would have settled on rocks, breaking down organic matter to create soil. Over time, seeds from nearby continents would have been transported by wind or ocean currents and taken root on the island. Birds were also important seed dispersers.

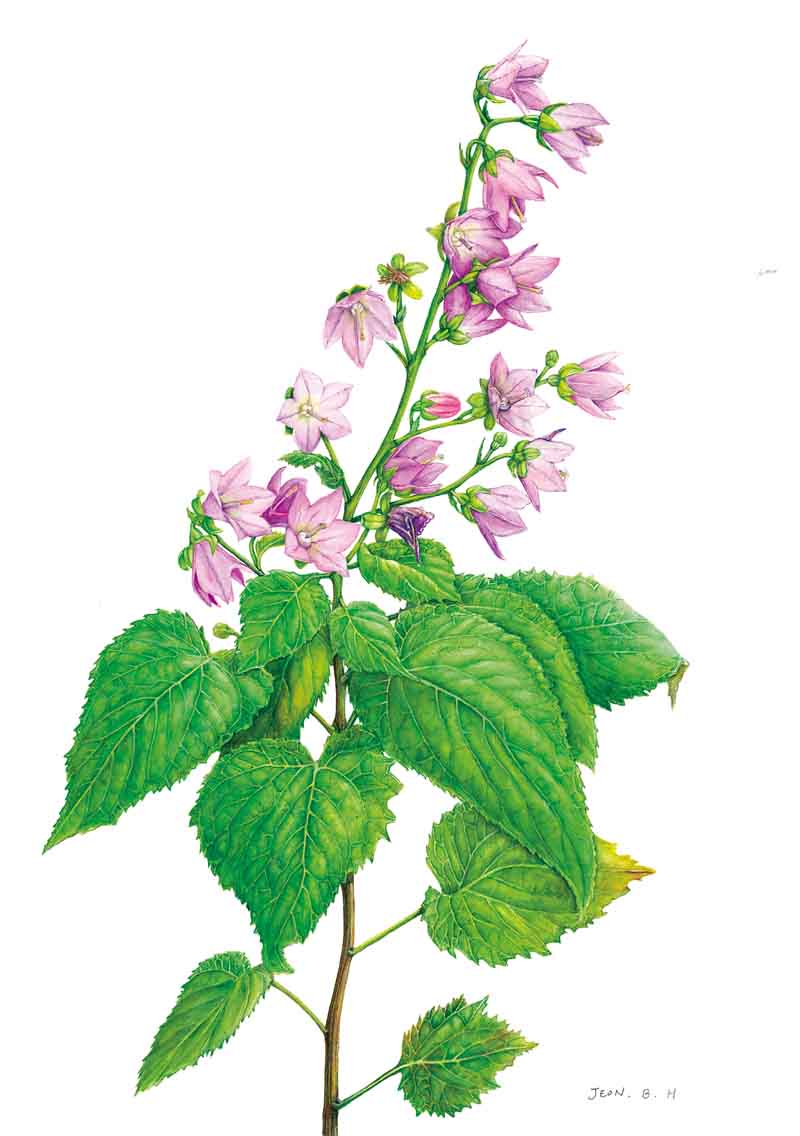

The erect ladybell, endemic to Ulleungdo, grows along the coastline. Declared a new species in 1997, its small population requires protection.

© Jeon Byeong Hwa

.jpg)

The Ulleungdo liverleaf, with leaves about three times larger than those of the Asian liverleaf found on the mainland, produces hairless ovaries and fruit.

© Jin Ahn Joung

But plant species from the mainland would have struggled to survive Ulleungdo’s harsh conditions. The earliest plants to arrive must have had small, light seeds or spores, and were extremely resilient. To withstand the craggy terrain, hot and dry weather, and strong winds, their roots had to be well developed. They also likely developed the ability to produce and spread offspring through self-pollination or asexual reproduction. The small number of plants that managed to survive expanded their area of coverage, and other species that subsequently arrived struggled to make Ulleungdo home.

Through repeated cycles of herbaceous plants growing, dying, and decomposing, the island’s soil became thicker and richer, allowing an early ecosystem to develop. Thereafter, small trees, insects, birds, and small mammals started populating the island, causing food chains to be established and making the ecosystem more complex. Over time, forests spread. After this long and arduous process, Ulleungdo’s ecosystem became stabilized.

The small minority of plant populations that survived did not retain their original traits. The remoteness of Ulleungdo inevitably led to low genetic diversity. Mutations, genetic drift, and natural selection over a long geological period produced distinct species, with morphologies significantly different to those of pioneer species.

The Chusan aster, discovered along the coast of Chusan Village, is a natural hybrid that was recognized as a new species in 2005.

© Shin Hangsuk

Engler’s beech thrives in Ulleungdo’s steep mountainous regions and plays an important role in the island’s forest ecosystem. The species is not found anywhere else in Korea.

© Hongju Kim

UNIQUE TRAITS

Ulleungdo is highly unique in terms of phytogeography — the geographic distribution of plant species. It has a mix of warm temperate evergreen broad-leaved trees, such as the common camellia and Thunberg’s bay-tree, and cold climate plants, such as the short-fruit rosebay. The island’s oceanic climate facilitates this coexistence. Unlike inland regions at the same latitude, such as Gangneung or Pocheon, Ulleungdo has mild and humid conditions owing to warm sea currents.

The island is also home to large plant colonies that are not found anywhere on mainland Korea, the most notable species being Engler’s beech in Taeha Village. This deciduous broad-leaved tree also grows in the Japanese archipelago. On Ulleungdo, however, it has unmatched ovate leaves with finely serrated edges and a shorter flower cluster. Its bark is also distinct, gray with shallow furrows. Along with Engler’s beech, colonies of Ulleungdo hemlock and Ulleungdo white pine, also in Taeha Village, have been designated and protected as natural monuments.

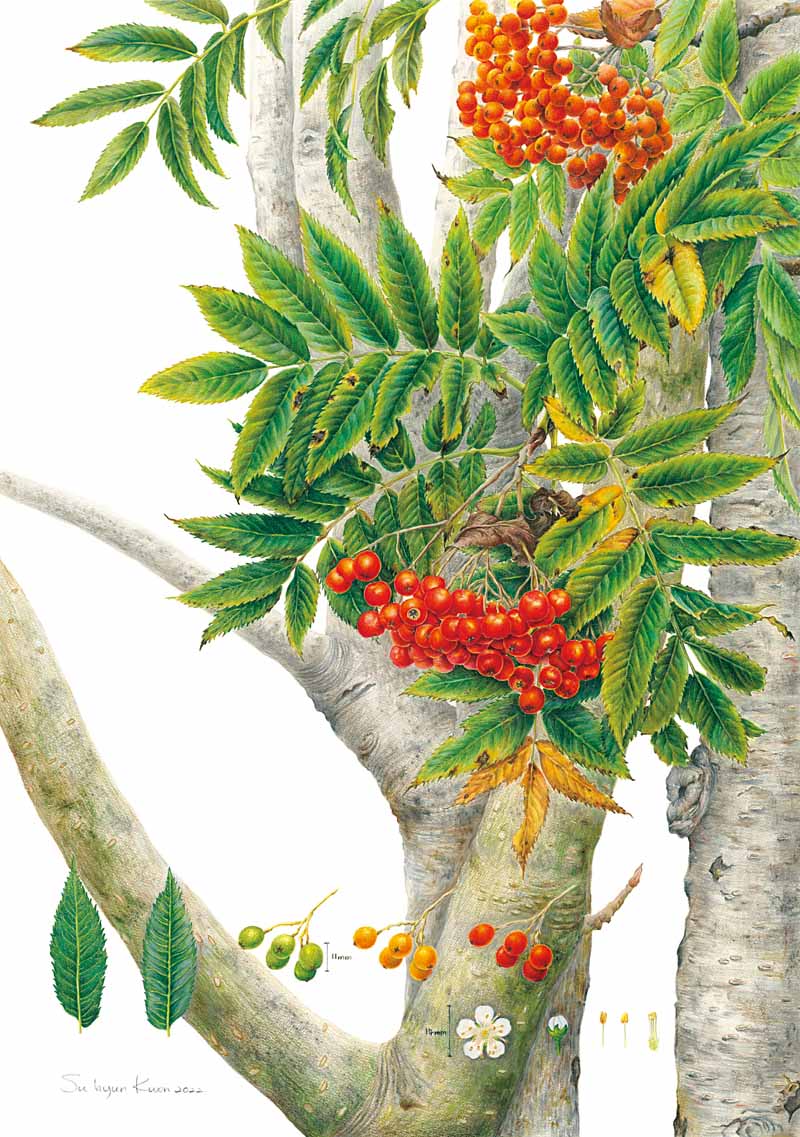

The Ulleung rowan grows in a colony around the summit of Seonginbong. It was declared a new species in 2014.

© Su Hyun Kwon

Further distinguishing Ulleungdo is a wealth of endemic species that have adapted to the environment. Much of the island’s plant life resembles mainland counterparts, but exhibits slightly different characteristics. In general, evolution tends toward one of two extremes: dwarfism or gigantism. On Ulleungdo, the latter is true.

One example is the Ulleungdo raspberry, which grows throughout the island. Descending from the mainland’s commonly found Korean raspberry, Ulleungdo’s variant looks similar but is taller, with larger leaves and flowers. But size isn’t the only difference; this raspberry has no thorns on its stems. With no herbivorous mammals like deer or wild rabbits on the island, the plant never developed a defensive mechanism. Research has found that the Ulleungdo raspberry went through at least two independent evolutionary processes. Similarly, the Ulleungdo liverleaf, which also evolved in geographic isolation, is an evergreen with leaves about three times larger than the smaller, deciduous Asian liverleaf found on the mainland.

The Chusan aster represents another type of evolution: hybridization through genetic exchange. Recognized as a new species, it grows on the island’s coast alongside the Ulleungdo aster and seashore spatulate aster. The size of its flower and the shape of its leaf and involucrum (the leaf-like whorl that protects the flower or bud) are a mix between the two other types of asters; hence, it is presumed to be a natural hybrid. The Chusan aster was named after Chusan Village, where it was discovered in 2005.

The Ulleung dendranthema blooms white in autumn. Forming a colony in Nari Basin, it is protected as a natural monument due to its small population.

© Kim jung a

BIODIVERSITY INDICATOR

When plant taxonomists discover what they believe to be a new species, they compare the specimen to the literature. If it possesses distinct morphological characteristics, it is officially declared as such.

The Ulleungdo elder, found in both mountainous and coastal parts of the island, is able to withstand strong sea winds.

© Hongju Kim

Research on Ulleungdo’s plant life was initiated by the Japanese botanist Takenoshin Nakai in 1910, during the colonial period. Nakai ended up announcing the discovery of dozens of new species to the academic community, including woody plants such the aforementioned Engler's beech, and herbaceous plants like the Ulleungdo raspberry and Ulleungdo liverleaf. That’s why their scientific names carry Nakai’s name, despite being plants endemic to Ulleungdo.

Korean research began in earnest in the 1950s. Until the mid-1980s, it was primarily centered on plant taxonomy; thereafter it expanded to plant ecology. With the remarkable technological advancements of the Human Genome Project, which began in 1990, genetic analysis was newly incorporated into plant taxonomy. This has since allowed for more in-depth studies of Ulleungdo’s flora.

One case in point is the Korean bellflower, an endemic plant that grows throughout the island. Discovered by Nakai in 1922, its progenitor species is the spotted bellflower found on the continent. A few years ago, the Korean bellflower was also discovered on Dokdo, a group of nearby islets. This prompted the National Institute of Biological Resources to analyze its chloroplast genotype. The findings raised the possibility that the Dokdo Korean bellflower was a stepping stone for the genesis of its Ulleungdo counterpart.

The Ulleungdo stonecrop blooms in yellow clusters from May to October. It is found in the island’s rocky areas, as well as on Dokdo.

© Su Hyun Kwon

In this way, the majority of Ulleungdo’s endemic plants have undergone an evolutionary process by which, rather than splitting into two or more distinct species, an original species transforms into new ones. This is rarely seen anywhere else in the world.

Beyond their importance as regional or national resources, Ulleungdo’s endemic plants are also important indicators of global biodiversity. However, many species are endangered, including the Ulleungdo cotoneaster and Ulleungdo hare’s ear, both on the Red List of Threatened Species maintained by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. This calls for a wide, collaborative effort to protect the island’s endangered plants, especially in terms of habitat protection and management, species conversation and propagation, and elimination of potential threats.