Mokpo has been the hometown and creative stage for many renowned figures in the arts. From literature and dance to the fine arts, traditional music, and popular songs, the city has produced an extraordinary range of talent across different disciplines. To trace the story of Mokpo’s artists is, in effect, to retrace the history of Korean art itself.

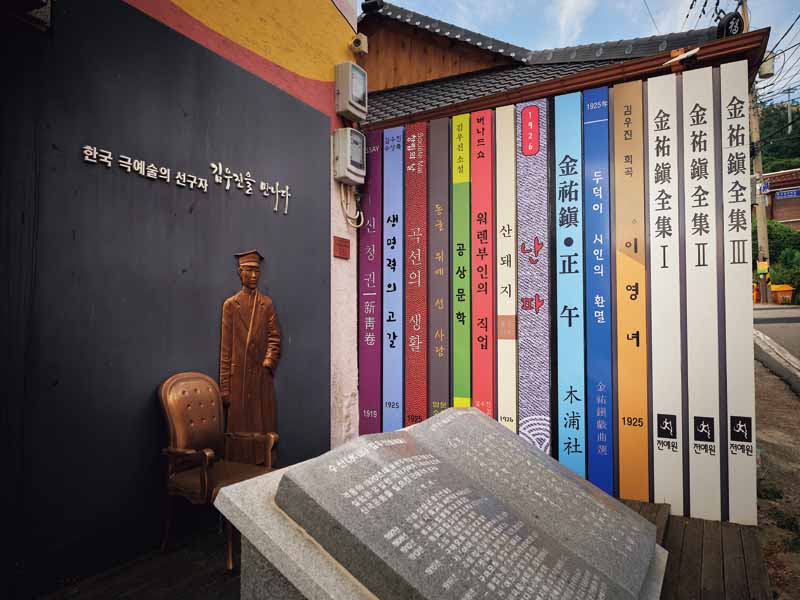

Playwright Kim U-jin, who grew up in Mokpo, brought fresh vigor to modern Korean theater with his profound knowledge and pioneering spirit. In 2014, sculptures, murals, and text panels were installed in a street near Yudalsan Sculpture Park to commemorate the life and work of the famous dramaturg. Pictured is the Firefly Small Library, dedicated to Kim’s legacy.

© Lee Min-hee

There’s a saying in Mokpo: “Of every four people you brush past on the street, one is an artist.” This suggests how artistically rich the city is. Paintings and calligraphy hang not only in homes but also in cafés, restaurants, bars, and inns. With striking ease, residents sing challenging pansori, folk songs from Namdo (South Jeolla Province), and yukjabaegi — pieces usually reserved for seasoned professionals. And whenever a melody drifts through the air, people instinctively move to the rhythm.

Despite being a relatively small city with a population of about 210,000, Mokpo has a reputation as home to many artists and art enthusiasts. Even more than Gwangju, once the administrative center of South Jeolla Province, it spearheaded the renaissance of modern and contemporary arts in the Namdo region, fueled by its inherent artistic potential and eager embrace of Western culture.

INFLUX OF FOREIGN INFLUENCES

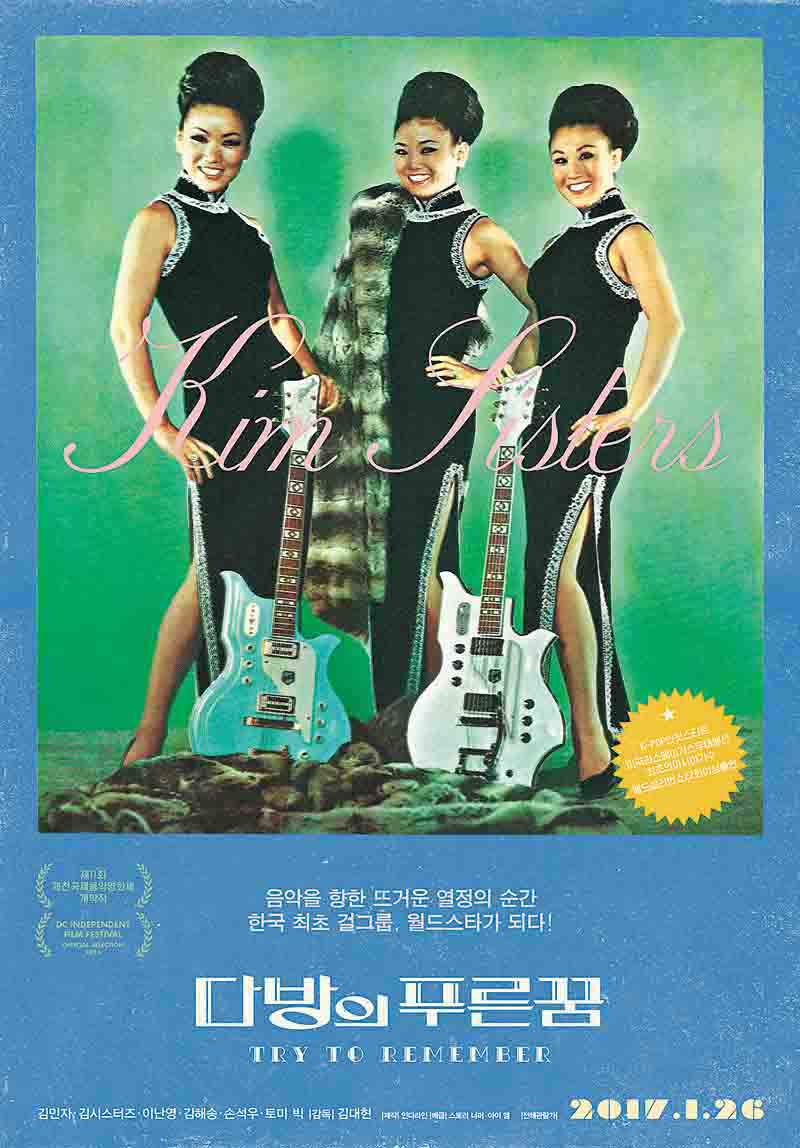

Poster for director Kim Dae-hyun’s documentary Blue Dream of the Teahouse, titled after the eponymous song by Mokpo-born singer Lee Nan-young. The film traces the musical journey of Lee, her composer husband Kim Hae-song, and their daughters, who formed the Kim Sisters, one of Korea’s earliest girl groups.

Courtesy of INDELINE

One distinctive local tradition is sandai, a dynamic festivity of the islands along the southwestern coast where the whole community — particularly young men and women — would gather to eat, dance, and sing together. This lively street celebration was a common sight until the 1990s, but the subsequent migration from the islands to the mainland has made it rare. The term derives from sandaehui, performances held during major national events in the Goryeo (918–1392) and Joseon (1392–1910) dynasties, with sandae referring to an outdoor stage built for this purpose.

With more than a thousand islands scattered off its coast, Mokpo naturally absorbed these local traditions. When influences from the United States, China, Japan, and Europe flowed into the city during the modern era, they merged with the native culture, becoming a powerful catalyst for artistic creation. Mokpo residents readily accepted these cultural influences. During this time, as schools were founded, a new educated class emerged to lead artistic and cultural activities. American Presbyterian missionaries also played a significant role in this process. Minister Eugene Bell, dispatched to Korea in 1895, established Jeongmyeong School (today Jeongmyeong Girls’ Middle School) and Yeongheung Seodang (now Yeongheung High School) in 1903. These institutions introduced Western-style education in music, art, and theater, laying the foundation for a modern cultural life.

Meanwhile, Mokpo’s growth as a port spurred industries such as shipping, trade, shipbuilding, and logistics, which gave rise to a burgeoning merchant class. These prosperous families became eager consumers of newspapers, magazines, music, theater, literature, and film. Many of their children studied in Japan or Europe and returned home steeped in modernist art, further enriching the city’s cultural landscape.

Among the figures emblematic of this era was playwright Kim U-jin (1897–1926). After studying English literature at Waseda University in Tokyo, where he formed the Theatrical Arts Association, a drama research group, Kim returned to Mokpo and published forty-eight poems, five plays, and twenty critical essays. Drawn to modern Western thought, he rejected traditional conventions and envisioned radical reform. His masterpieces Shipwreck (Nanpa) and Wild Boar (Sandoeji), regarded as Korea’s first expressionist plays, challenged a theatrical world dominated at the time by melodrama. Kim was also renowned for his romance with Yun Sim-deok (1897–1926), the most popular singer of that era and Korea’s first professional soprano, whom he had met in Japan when she was studying at the Tokyo Music School (now Tokyo University of the Arts).

Lee Nan-young debuted with OK Records in 1934 and rose to national stardom the next year with her massive hit “Tears of Mokpo.” Pictured is an LP album of her hit songs released by LKL Records in the 1960s.

© National Museum of Korean Contemporary History

Western culture also reshaped the city’s music scene. Singer Lee Nan-young (1916–1965) became a household name with her 1935 hit “Tears of Mokpo,” dubbed by some as Korea’s “national anthem.” Two years later, she married composer Kim Hae-song and her career blossomed. The couple were heavily influenced by Western popular music, and “Blue Dream of the Teahouse” (1939), which mixed swing and blues styles, was a masterpiece that led to Lee’s reevaluation in relation to Korean jazz history.

HEART OF HONAM’S ART SCENE

If Paris has Montmartre, Mokpo has Ogeori, a bustling five-way intersection. During the Japanese occupation, this busy crossroads linked the city’s port, the railway station, and the Korean and Japanese residential districts. In the 1950s, cultural facilities such as ateliers, galleries, and theaters clustered there, and the area soon developed into the heart of the city’s social, cultural, and economic life, a role it maintained through the mid-1990s. During the Korean War (1950–1953), many artists evacuating from Seoul had come to Mokpo, accelerating its rise as a center of mainstream arts. Indeed, the Mokpo Federation of Arts and Culture Organizations (an umbrella body for local art groups) was established in 1958, four years before its nationwide counterpart.

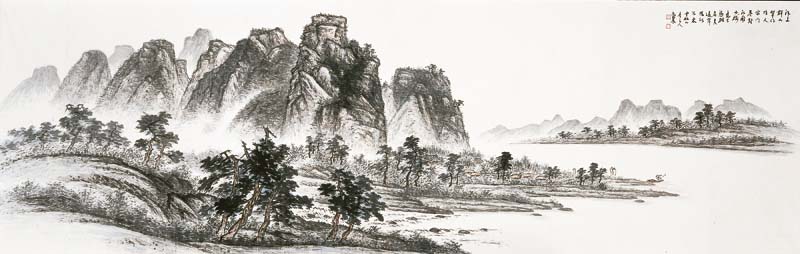

“Landscape” (Gangsan mujindo). Heo Geon. Early 1960s. Ink and color on paper. 101 × 285 cm.

Heo Geon was a painter who captured landscapes with striking realism using traditional ink and brush techniques. This masterpiece epitomizes the maturity of his style.

Courtesy of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

Writers, painters, photographers, and musicians all gathered at the crossroads dabang — teahouses — where creative exchange thrived. To be seen there was to be recognized as part of the cultural mainstream. From these teahouses emerged painters who would go on to shape Korea’s art world. A prime example is Heo Geon (1907–1987), a master of Southern School (literati) landscape painting, a genre reflecting the inner world of cultivated, learned scholar-painters. He was the grandson of Heo Ryeon (1809–1892), who studied under Chusa Kim Jeong-hui (1786–1856), an outstanding scholar and calligrapher-painter of the late Joseon period. Born into a family of painters, Heo Geon showed artistic talent from an early age. Settling in Mokpo as a young man, he was active in the crossroads teahouses and devoted his entire life to artistic pursuits in the city. These spaces also fostered early modern art, driven by Western-trained painters who had studied abroad. In short, the Mokpo Ogeori became the artistic hub of the Honam region, encompassing North and South Jeolla Provinces.

At the same time, as local newspapers and literary magazines flourished, the teahouses became hubs of literary creation and criticism, leaving a significant mark on the development of Korean literature. The Mokpo Ogeori thus bears the legacy of major names in Korean literary history, including the aforementioned playwright Kim U-jin, novelist Park Hwa-seong (1904–1988), playwright Cha Beom-seok (1924–2006), and literary critic Kim Hyeon (1942–1990).

A scene from Active Volcano, performed in 2024 by the National Theater Company at the Myeongdong Arts Theater to mark the centennial of playwright Cha Beom-seok’s birth. The play portrays the realities of rural life amid the turbulence of the late 1960s. Born in Mokpo, Cha was a realist who helped popularize modern Korean theater.

Courtesy of the National Theater Company

FROM PANSORI TO POP

Mokpo also played a vital role in the performing arts. The founding of the Mokpo Traditional Music Association in 1962 ensured systematic preservation of the region’s musical heritage, with pansori masters teaching and performing there. In dance, Lee Mae-bang (1926–2015) stands out. Acclaimed as “the master of Honam dance,” he became the only person in Korea to possess National Intangible Cultural Heritage status in two categories: seungmu (Buddhist monk’s dance; designated in 1987) and salpurichum (ritual dance of cleansing and casting off misfortune; designated in 1990). Performed with long white extended sleeves that look like scarves, salpurichum originated in the improvised dances of shamans during rites, gut. Lee’s artistry in both genres was so profound that it gave rise to his own distinctive school of dance, known as the Lee Mae-bang Style.

Dongchun Circus members perform their signature plate-spinning act. Founded in 1925, the troupe held its first-ever performance in Mokpo in 1927 and reached its heyday in the 1960s and ’70s. Today, the circus is based on Daebudo, an island that’s part of Ansan in Gyeonggi Province, where it continues its tradition with support from the municipal government.

Courtesy of Dongchun Circus

Mokpo was also home to Korea’s first circus troupe, the Dongchun Circus, founded in 1925. It ushered in a golden age of domestic acrobatic performances in the 1960s and ’70s. Now relocated to Ansan, Gyeonggi Province, it remains the country’s last surviving circus troupe and continues this rare performance tradition.

The city’s influence on performing art has endured, setting the stage for many leading figures in K-pop and other Korean popular culture — such as comedian Park Na-rae, trot singer Park Ji-hyun, and Donghae from Super Junior — who trace their roots back to Mokpo.

In many ways, Mokpo is a compact archive of Korea’s arts and culture, past and present. From traditional painting and pansori to modern music, literature, and even K-pop, the city has long been a place where creativity thrives, its rich artistic heritage continuing to inspire Korea’s cultural landscape today.