Gochang in North Jeolla Province delights visitors with its fertile land and beautiful landscape, but its sunny hills and winding valleys also keep heartbreaking memories of a failed peasants’ revolt from the waning years of Korea’s final dynasty.

The high-speed KTX train departing from Yongsan Station in Seoul deposited me at Songjeong Station in Gwangju after one hour and 40 minutes. Driving with a friend who met me at the station, I found a billboard beckoning us to the town of Gochang. “Welcome to Gochang, the first capital of the Korean peninsula. Home of Mt. Seonun, beautiful all year round, and the sacred site of the Donghak Peasant Revolution.” Indeed.

Gochang is where the flag of the farmers’ revolt was first raised in 1894, when the Joseon Dynasty was falling. It is also the gravesite of the defeated peasant warriors. Next to the billboard, a banner appealed for donations: “Join in the fundraising to erect a statue of General Jeon Bong-jun.” There already are several government-funded statues memorializing the revolution and its leaders. But this time, the local residents intend to build a statue of the revolution’s foremost leader of their own accord.

The rock-carved seated Buddha by the path leading up to Dosol Hermitage at Seonun Temple in Gochang dates back to the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). Measuring 15.7 meters high and 8.5 meters wide at the knees, it is one of the largest rock-carved Buddhist images in Korea. In the 1890s, warriors of the Donghak Peasant Revolution prayed in front of the Buddha for success in battle.

Birthplace

Beyond vast fields, the footprints of the revolution lead to the small, tiled-roof house of Song Du-ho (1829-1895) in Juksan village, Jeongeup, North Jeolla Province. I came here first because I wanted to pay a silent tribute to a revolutionary who was executed 126 years ago. The site has no front gate. A concrete column announces it as the “Birthplace of the Donghak Peasant Revolution.” From here, dreamers of a better life scattered the seeds of revolution that challenged Korea’s last monarchy. They promised each other that they would fight to the death.

The outcome of their vows was the so-called sabal tongmun, or “rice bowl circular,” which features 22 signatures written along the rim of an overturned rice bowl. No one could determine who signed first in the circle of names, so the instigators remained hidden.

The format mirrored a roundtable gathering in medieval Europe; the identity of the head of the group and ranking of individuals could be concealed.

This document is evidence that the Donghak Peasant Revolution was a well-planned, grassroots effort to end long years of tyranny and corruption. It includes a four-point code of conduct that essentially called for armed resistance. It urged residents to storm the magistrate’s office and, from there, march on to Seoul. Donghak, meaning “Eastern Learning,” was a homegrown academic and reform movement against Western influences represented by Christianity and imperial powers.

That the document still exists at all is practically a miracle. It was discovered by chance 53 years ago, hidden under the floorboards at the home of Song Jun-seop, a descendant of Song Du-ho. When the revolution collapsed, government soldiers who had been sent to put down the strife condemned the place as a “village of rebels,” and indiscriminately massacred the residents and burned down their houses. The circular was hidden inside the family’s genealogical record, which escaped the destruction.

The house right in front of the one where the revolution was plotted is where my friend’s grandfather used to live. My friend’s eyes began to glisten as he looked from one house to the other. Not far off is the Donghak Revolution Memorial Tower, erected by descendants of the original revolutionaries. And nearby is also the Donghak Peasant Army Memorial Tower, honoring the countless, nameless heroes who fought for change.

The first volley in the revolt was an anti-government protest in Gobu. It was a success, but the revolt was ultimately crushed at Ugeumchi, a mountain pass in Gongju to the north. The peasant warriors wielded spears, no match for the guns of the government and the Japanese soldiers who allied to subdue the revolt.

A bowl of rice sitting before the memorial speaks for the reason why those starving farmers took up their pickaxes and sickles. In those days, rice needed to be shared for the people to survive. As I looked over the vast fields, the image of the hungry farmers marching on Seoul overlapped with that of Spartacus leading warrior slaves in their march on Rome. Both revolutions were crushed.

Seonun Temple is embraced by the largest concentration of camellia trees in Korea. The camellias here bloom from late March to mid-April, adorning the temple grounds with their gorgeous red flowers and lush green leaves.

Manseru (Pavilion of Eternity) at Seonun Temple was built as a lecture hall in 1620. Destroyed by fire, it was rebuilt in 1752 and its original name, Daeyangnu, was changed to Manseru. The interior beams and rafters are made of natural unprocessed timbers.

Temple and Sea

The next stop was Seonun Temple. There, I wanted to absorb the quietude and wash away the dust in my mind. But the temple was abuzz with people who had come to see the camellia trees profuse with red flowers behind the main hall.

Seonun Temple, nestled on the northern slope of Mt. Seonun (Zen Cloud), was founded in 577 by two monks: Geomdan of Baekje and Uiun of Silla. At the time, the two neighboring states were at war, leaving many people displaced. The two monks joined forces to save the refugees and built a haven where communal life began. In this way, the temple was originally a refugee relief center. Accordingly, some 1,300 years later, the peasant army prayed for the success of their uprising in front of the rock-carved Buddha at Dosol Hermitage, about 2.5 kilometers up the slopes of the mountain behind the temple.

Leaving Seonun Temple, I headed for a beach known for its “10 li of clear sand,” called Myeongsasimni. The beach faces Gyeokpo port in Buan, and a dense forest of pine trees hundreds of years old lines the strip of fine, white sand that stretches more than one kilometer. The scent of pine in the spring breeze seemed to cleanse my senses. The wind whipping through the pines whispered like water boiling in a teapot.

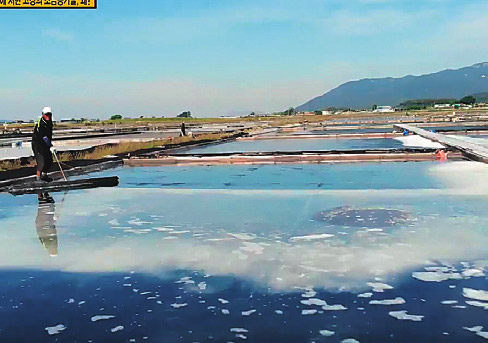

Beyond the sand, the tidal flats were vast and endless. The west coast of Korea has the highest tidal range in the world. Day after day, the sea and land rotate; a spot where one stands one moment will soon become part of the sea again. The water here is so salty that people with skin trouble come to bathe in it, and those with neuralgia come for the hot sand baths. As I looked out across the tidal flats, Admiral Yi Sun-shin (1545-1598), Korea’s greatest naval commander, came to mind. It is said that when provisions ran out during the Japanese invasions of 1592-1598, he took a slice of the coast and gathered sea water there to evaporate it in the gigantic natural pot. The large quantity of salt thus produced was sold to buy thousands of tons of rice for his troops.

The barley fields of Hagwon Farm attract half a million visitors every spring. The Green Barley Field Festival is the largest festival in the region.

Small spirit poles (jangseung) serve as guideposts for barley fields in Gochang, which cover an area of about one million square meters.

As I looked over the vast fields, the image of the hungry farmers marching on Seoul overlapped with that of Spartacus leading warrior slaves in their march on Rome. Both revolutions were crushed.

Some 1,600 dolmens can be found in Gochang County, the largest cluster of megalithic tombs in Korea. Along with the Hwasun and Ganghwa sites, the Gochang Dolmen Site was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2000.

A local farmers’ band performs in the yard in front of Gochang Town Fortress. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, performances of traditional music and dance were given here, as well as at the nearby birthplace of Shin Jae-hyo (1812-1884), a master singer and teacher of pansori, every weekend from spring to autumn.

Grilled Eels

Once you’ve stepped foot in Gochang, you can’t leave without having grilled jangeo (eels) and bokbunja (Korean black raspberry) wine. Gochang is famed for its specialty of eels caught in the Pungcheon River, right where it meets the sea. These eels are a popular health food.

Off a main thoroughfare, in a lonely spot near the fields stands a restaurant with a lengthy name: “Hyeongje Susan [Brothers’ Fishery] Pungcheon Jangeo.” This is a place that local foodies keep to themselves. It has a large garden and spacious interior.

The owner of the restaurant grills fresh eel over charcoal, applying a special marinade that contains over 200 ingredients, including medicinal herbs, grain enzymes and herb-based liquor. The side dishes on offer vary according to the season, and the ingredients are all organically grown. The restaurant’s home-brew raspberry wine danced on my tongue, making me feel stronger and younger.

Gojeon-ri Salt Village

Ungok Ramsar Wetland

Gochang Dolmen Museum

Gochang Pansori Museum

Dolmen Clusters

Early the next morning, I looked around the Gochang Dolmen Museum located in town, and then went to the village of Daesan to see the dolmens in their natural state. Every path from the village entrance to the midslope of the mountain is lined with these monoliths as the great mountain hosts a large outdoor museum of ancient stone tombs. Each dolmen is numbered – the higher up the mountain, the lower the number. I wanted to see No. 1 at the summit, but exhaustion took over. I gave up.

Sixty percent of the world’s dolmens are found on the Korean peninsula, and about 1,600 of these, the largest cluster, are in Gochang. The Gochang Dolmen Site, along with the Hwasun and Ganghwa sites, was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2000, recognized for its unique and varied group of dolmens that reveal changes in construction methods.

It could be said that the entire county of Gochang constitutes a cultural heritage site. In 2013, Gochang was also designated as a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve, in recognition of its beautiful natural environment and biological diversity.

In the afternoon, hobbling on tired legs, I went to see the green barley fields of Hagwon Farm. Every April, when the yellow rapeseed flowers bloom, the whole area turns into a tourist attraction bustling with tens of thousands of visitors from across the country. As I emerged from the furrows of fresh green barley sprouts, it began to rain. Just as flowers must fall before fruit ripens, beauty must be forsaken for new life to be born. Suddenly, I felt there was something miraculous about the new sprouts in the fields getting wet under the spring rain. This was a trip not for taking in new sights, but for finding a new way of seeing things.