Korean folk paintings were produced and appreciated by common people. Amateur painters, their skills not comparable to professional artists, created an enchanting world by employing a symbolic system where a set of motifs were assigned specific meanings.

“Mt. Geumgang.” Late Joseon Dynasty. Ink and light color on silk. 50.2 × 34.6 cm. Sun Moon University Museum.

“Flowers and Birds.” Late Joseon Dynasty. Ink and color on paper. 69.1 × 41.2 cm. Sun Moon University Museum.

Landscapes

Under the deep-rooted influence of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism, East Asia has a long tradition of living in harmony with nature. Landscape painting (sansuhwa, literally “painting of mountain and water”) was a genre of art originating from the heart-felt affinity and unity with nature shared in this cultural sphere. For many artists, nature was their most important and favorite subject.

At first, minhwa landscapes imitated works of fine art, most notably the “true-view” landscape paintings (jingyeong sansuhwa) by Jeong Seon (1676-1759). True-view paintings, with their simplified expression of objects in bold brushstrokes, were relatively easy for amateur artists to emulate compared to the detailed depictions used in other genres of painting.

Flowers and Birds

Traditional paintings of flowers and birds (hwajodo) were generally a faithful representation of natural beauty. On the other hand, minhwa works of flowers and birds were replete with the symbolism of a happy marriage, which imbued them with qualities both decorative and talismanic. The most common motifs were flowers such as peonies, lotus blossoms, plum blossoms, chrysanthemums, daffodils, magnolias, orchids and pomegranates; and birds such as the pheasant, phoenix, crane, wild goose, duck, chicken, white heron, mandarin duck, swallow, nightingale and sparrow.

Probably the most popular flower motif was the peony, which stood for wealth and nobility. The pomegranate reflected wishes for many children, as symbolized by the numerous seeds tightly packed in the fruit. The pheasant, mandarin duck and domestic duck were always depicted in pairs as icons of conjugal love and domestic bliss.

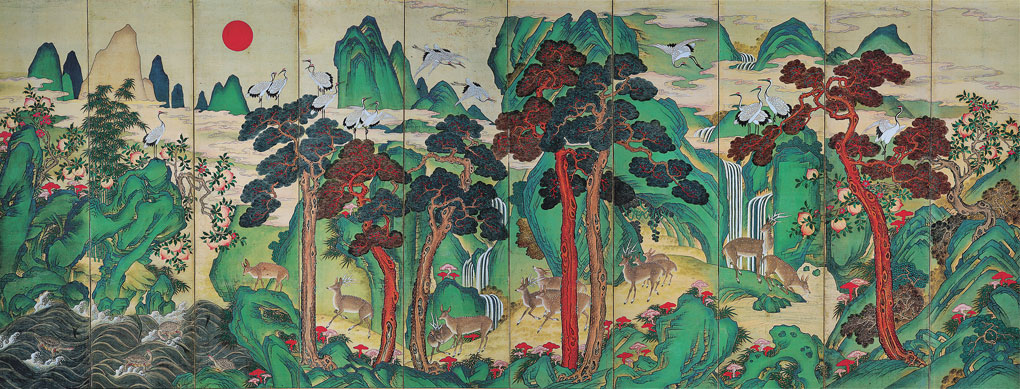

“Ten-panel Folding Screen with Ten Symbols of Longevity.” Latter half of the 18th century. Ink and color on silk. 210 × 552.3 cm. Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art.

Ten Symbols of Longevity

Conveying universal wishes for health and long life, paintings of the ten symbols of longevity (sipjangsaengdo) feature the sun, clouds, water, mountains, rocks, turtles, cranes, pine trees, deer and the mushroom of immortality. Over time, the genre expanded to encompass 12 symbols, including peaches and bamboo, though all 12 are still referred to as the “ten symbols.” The symbolism presumably originated in primitive religion based in shamanism, which venerated nature and its forces.

In early human societies, shamanism often had the status of a state religion, wielding absolute power over people across classes. The shamanistic way of thinking had been entrenched in the Korean subconscious and its influence continued even after Buddhism became popular. This spiritual tradition yielded paintings of the ten longevity symbols that, using bold and vibrant colors, manifested unique Korean color sensibilities.

“Twelve-panel Folding Screen with Taoist Immortals” (detail). Choe U-seok (1899-1964). Date unknown. Ink and color on silk. 181.5 × 285 cm (each six-panel screen). National Folk Museum of Korea.

Taoist Immortals

The notion of Taoist immortals (sinseon) has a long history dating back to Gojoseon, or Old Joseon, the first state in Korean history. Dangun, the legendary founder of this ancient state and progenitor of the Korean people, is said to have become an immortal. Koreans used to regard immortals not as purely mythical beings but as a state that humans could achieve through spiritual discipline. They believed that by leaving the mundane behind and contemplating themselves and the world, they would be able to attain ultimate awakening and become an immortal.

Eventually, paintings of Taoist immortals came to represent hopes for a peaceful existence at one with nature, free from suffering.

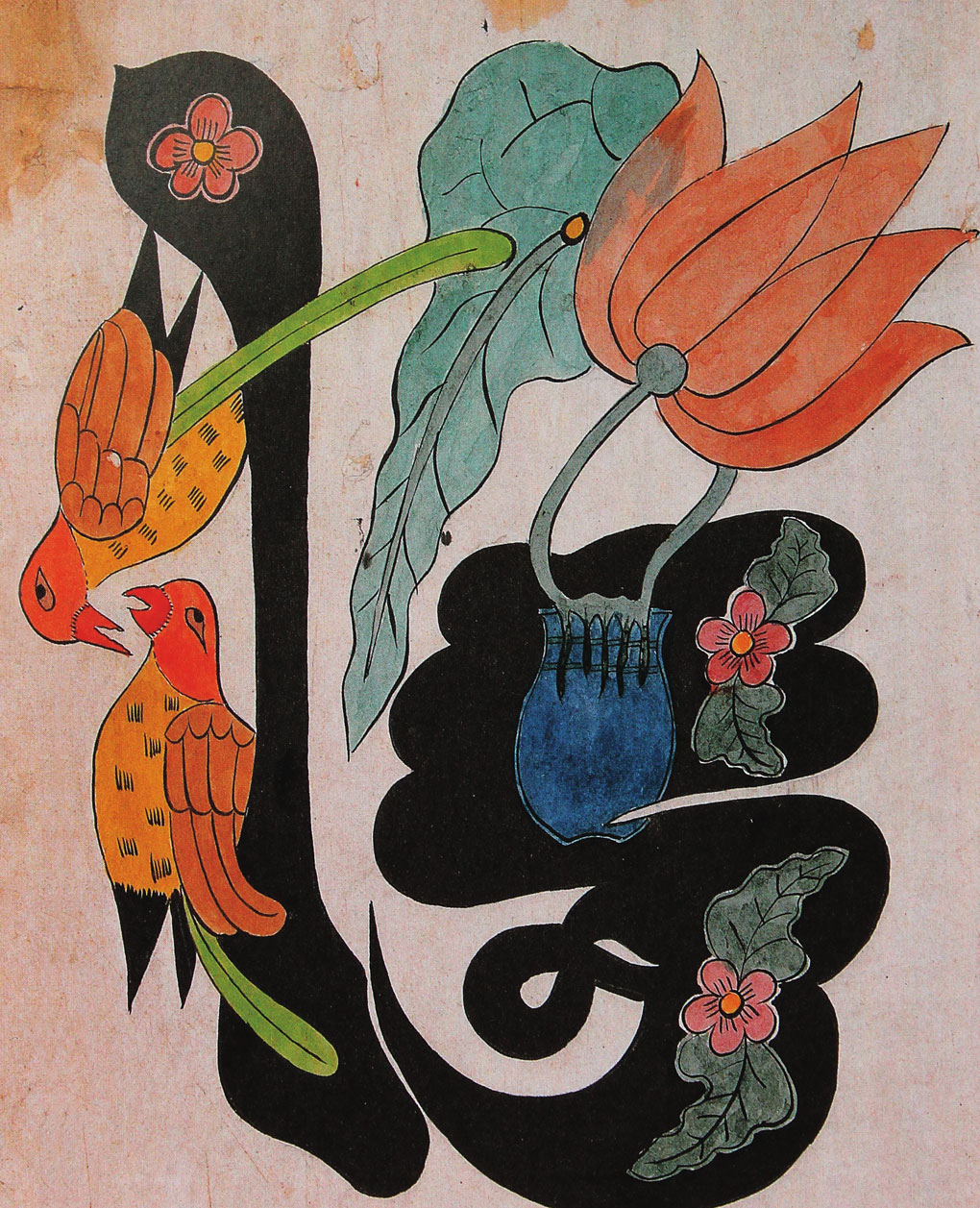

“Pictorial Ideograph: Brotherly Affection (悌).” Early 20th century. Ink and color on paper. 55 × 33 cm. Private collection.

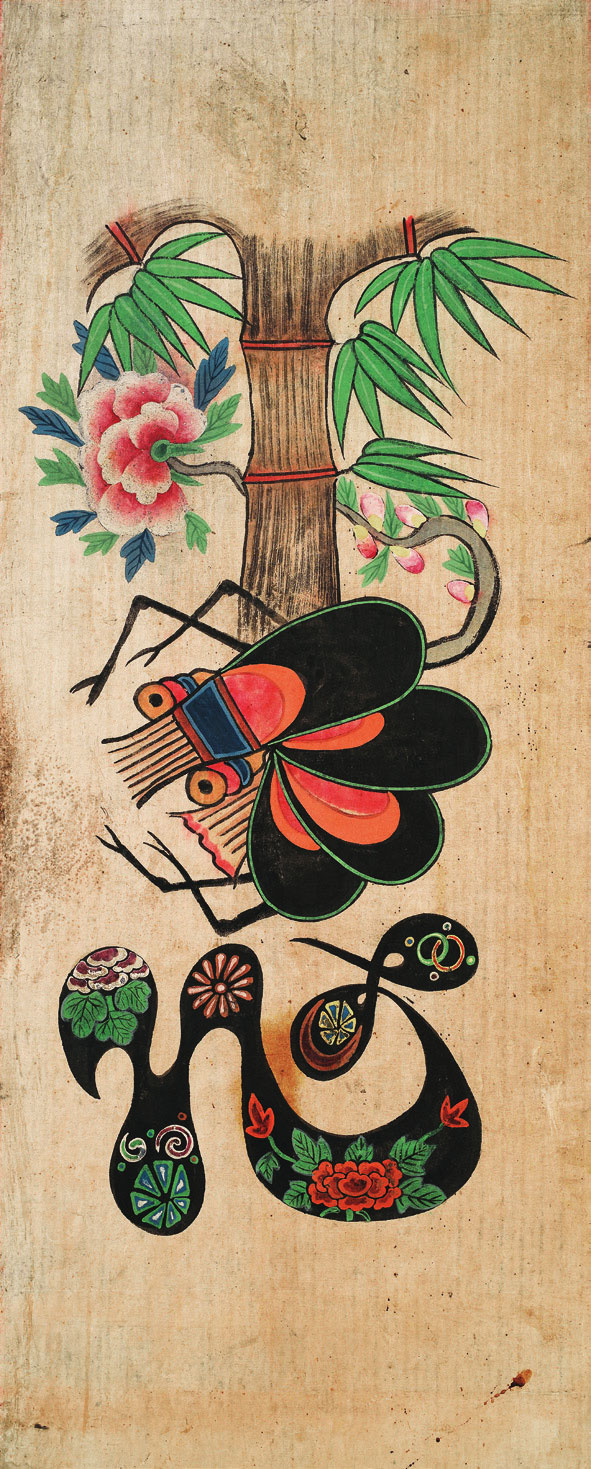

“Pictorial Ideograph: Loyalty (忠).” 19th century. Ink and color on paper. 90.2 × 34.2 cm. Private collection.

Pictorial Ideographs

Another unique type of minhwa is pictorial ideographs (munjado), consisting of classical Chinese characters representing the core tenets of Confucianism rendered with thick brushstrokes. Abstract motifs based in folk stories are painted in and around the strokes. The eight most frequently depicted virtues are: filial piety (孝), brotherly love (悌), loyalty (忠), trustworthiness (信), propriety (禮), righteousness (義), integrity (廉) and sense of shame (恥). Each character is decorated with images of animals, flowers, or other objects with corresponding meanings.

For example, paintings about brotherly love usually feature wagtails, which stand for brotherly cooperation, and Korean blueberry (sanaengdu) to symbolize harmony among siblings. Ideographic folk paintings are recognized for their indigenous combination of abstract and realistic expression.