From couriers to mobile apps – Korea’s delivery industry has achieved incredible advances over the past century. Progress didn’t come out of the blue, however. Let us take a brief look at how the delivery economy has evolved since the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910).

The first Westerner to serve as an advisor to the government of Joseon, Paul Georg von Möllendorff arrived in Hanyang (today’s Seoul) in 1882, leaving his previous position as German vice-consul in Tianjin of Qing China. There were few Westerners in Korea at the time, so one of his concerns was how he would have his meals. He needn’t have worried. In the evening, a Korean official visited his temporary residence with a few servants carrying a wooden litter for cargo. Beneath the cloth cover was a variety of dishes he had never seen before. Having had a similar experience in China, Möllendorff moved the dishes to his table and had his dinner.

“On the Way to Market in Snow.” Presumably Yi Hyeong-rok (1808-?). 19th century. Ink and light color on paper. 38.8 x 28.2cm. National Museum of Korea. This Joseon Dynasty painting depicts merchants heading for the market with their wares loaded on the backs of horses and oxen. It is part of an album allegedly painted by court artist Yi Hyeong-rok. © National Museum of Korea

Tributes and Gifts

Cargo delivery was an important economic activity in Joseon, supporting state management. The royal court relied heavily on tax in kind collected from its subjects across the country. For instance, for the monthly memorial rites for past generations of kings and queens held at Jongmyo, the royal ancestral shrine, provincial administrators gathered and sent the necessary goods, including grains, fish, fruit and salt, as well as paper and cooking utensils. Officials in charge of shipment of these goods supervised servants loading and moving the cargo using handcarts and boats. It was an important duty that could affect their position in government.

Delivery of regional products was also considered important by the wealthy yangban (nobility) living in the provinces who would make gifts to powerful figures in the capital. Kim Su-jong (1671-1736), a rich man in Buan, Jeolla Province, would often present his friends and dignitaries in Hanyang with local specialties, including dried seafood such as sea cucumber, abalone, mussels and octopus, as well as dried pheasant meat, pork and persimmons. As the region was famed for paper and bamboo products, fine mulberry paper rolls, fans, hats and combs were also highly prized among noblemen in the capital. From Buan, ships carrying this cargo sailed along the west coast and then up the Han River before reaching port at Mapo. There, the items were sorted and carried in handcarts or A-frame carriers to be delivered in person to each recipient. Kim’s servants did all of this work. In the process, Kim would make two copies of itemized lists of each delivery, one for himself and the other for the recipient.

Delivery by servants was also essential for yangban couples living apart. A historical record says that a woman of the Yi family in Andong, Gyeongsang Province, used to send to her husband, Kim Jin-hwa (1793-1850), who was serving in a public post away from home, foodstuffs such as octopus, yellowtail, flatfish, salt, red pepper paste (gochujang), soybean paste (doenjang) and other condiments. In return, Kim sent home mackerel, pollack, sweetfish, herring and beef.

The Neo-Confucian literati of Joseon looked down on monetary dealings, instead regarding exchange of goods as the proper conduct for a man of virtue. Some scholars of economic history believe that this way of thinking was behind the development of the delivery economy in Joseon society.

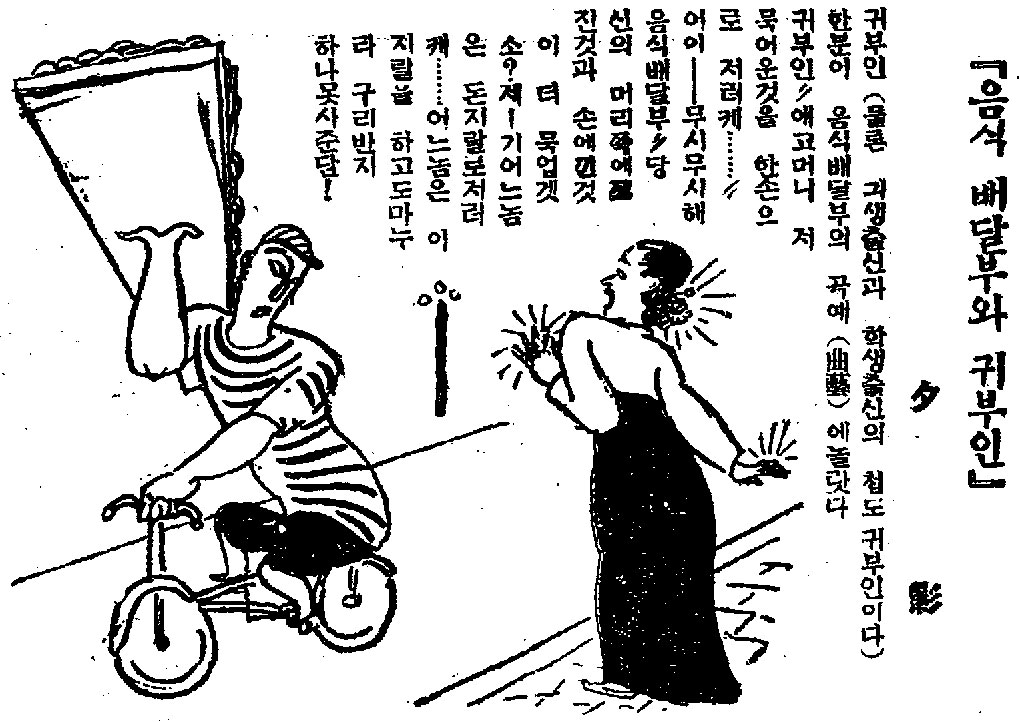

An editorial cartoon titled “A Food Deliveryman and a Lady,” by Ahn Seok-ju, from the April 5, 1934 issue of the daily Chosun Ilbo. The lady exclaims in amazement, “Oh, my… You carry such a heavy load with one hand!” and the deliveryman retorts, “I’d think those things in your hair and on your fingers are a sight heavier.” © The Chosun Ilbo

Lingering Class Awareness

In the early half of the 20th century, Korean society gradually underwent modernization, though under Japanese occupation. It was during this time that restaurants for the public started to appear in cities. Although the rigid social hierarchy of Joseon was apparently dissipating, age-old class distinctions still remained valid throughout society. Interestingly, it was this die-hard awareness of social class that gave rise to commercial food delivery. In the 1920s, seolleongtang (ox bone soup) was among the popular dishes served at restaurants in Seoul. The owners of these places were mostly butchers, considered the lowest class in pre-modern Korean society. Noblemen regarded it as unthinkable to eat among low-class customers in a restaurant run by a butcher, so they had the soup delivered to their home.

Back then, payments for home-delivered food were customarily made later, when the empty containers were picked up. This often resulted in disputes. There is a story about a seolleongtang restaurant in Jongno which had a customer who regularly ordered out but often avoided payment by being absent from home when the delivery man returned to collect the containers. Enraged after making several fruitless calls to the house, the delivery man went back with his friends and bullied a maid. He ended up being arrested by the police.

In addition to seolleongtang, the favorite dishes for delivery at that time were naengmyeon (cold buckwheat noodles) and tteokguk (rice cake soup), which were popular offerings at the restaurants that appeared in large numbers in Seoul and other cities. Orders were usually made via telephone, although telephone ownership still remained very low. After an order was received and the food was prepared, couriers delivered the food by bicycle, working the handlebars with the left hand and holding the food with the right. It was a feat as precarious as a circus stunt and quite a sight for onlookers.

A postman in the 1900s. Korea’s modern postal service started in 1884 with the establishment of the General Office of Postal Administration. In the early years, horse carts were used for mail delivery. © National Museum of Korean Contemporary History

Deliverymen pose in front of Sajeongok, a famous naengmyeon restaurant in Incheon, in this 1930s photo. The cold noodles served here were reputedly so tasty that orders came from as far as Myeong-dong in Seoul. © Bupyeong History Museum

“Morning,” a 1946 photograph by Limb Eung-sik, captures young women carrying basins full of flowers on the street in Busan. The photo is in the collection of the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. © Lim Sang-cheol

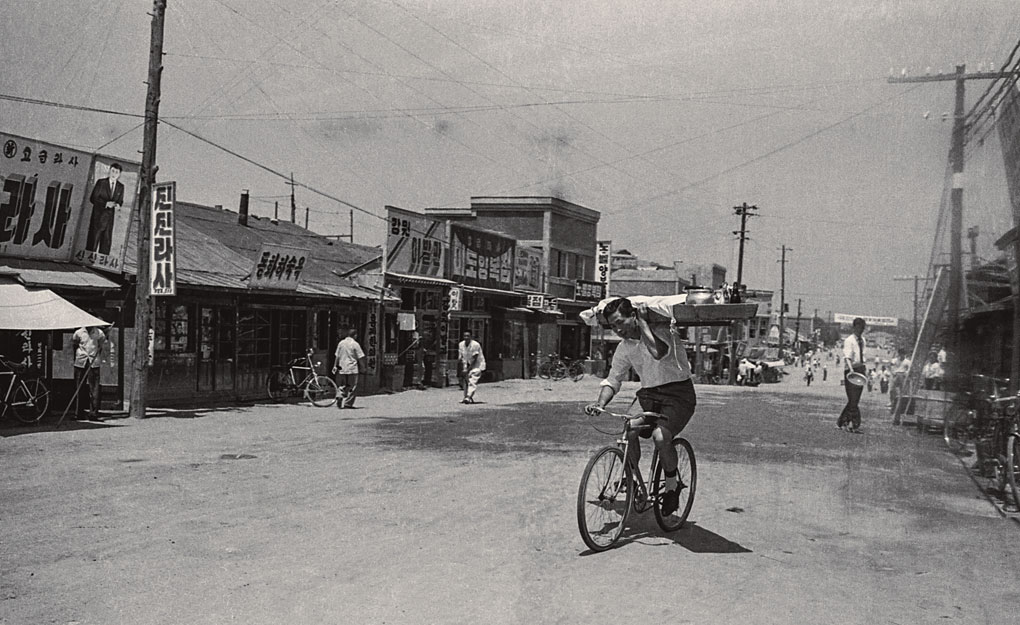

In this 1950s photo, a naengmyeon deliveryman puts on an exciting stunt show on the street in Sokcho. He is known to be the founder of a Hamheung-style cold noodle restaurant in the coastal town near the Demilitarized Zone. © Sokcho Municipal Museum

Handcarts and Bicycles

It was after permanent markets were established in the cities that delivery workers entered everyday urban landscapes. Vendors who could not leave their stalls to eat would order their meals from nearby eateries. Typically, the food was delivered by a woman with a large tray on her head stacked with bowls and dishes of food, walking gingerly to keep her balance. Even high-class traditional restaurants had a delivery menu offering dozens of dishes, which were carried on a wooden litter. Cooks and servers were at times dispatched to help at the banquets of wealthy families. Upscale Chinese restaurants also delivered food on demand as a complimentary customer service. Delivery services on a professional scale began with postal mail, newspapers and alcoholic drinks. Breweries supplied restaurants and bars directly by means of bicycle couriers.

After the nation’s liberation from Japanese rule and the subsequent Korean War, compressed economic development accelerated urbanization and industrialization. Domestic commerce grew rapidly, and logistics between wholesalers and retailers was largely facilitated by hired handcart couriers. Some of the couriers would buy the products themselves and resell them to retailers at the same price. Instead of distribution margins, they earned small profits by selling empty containers back to the wholesalers.

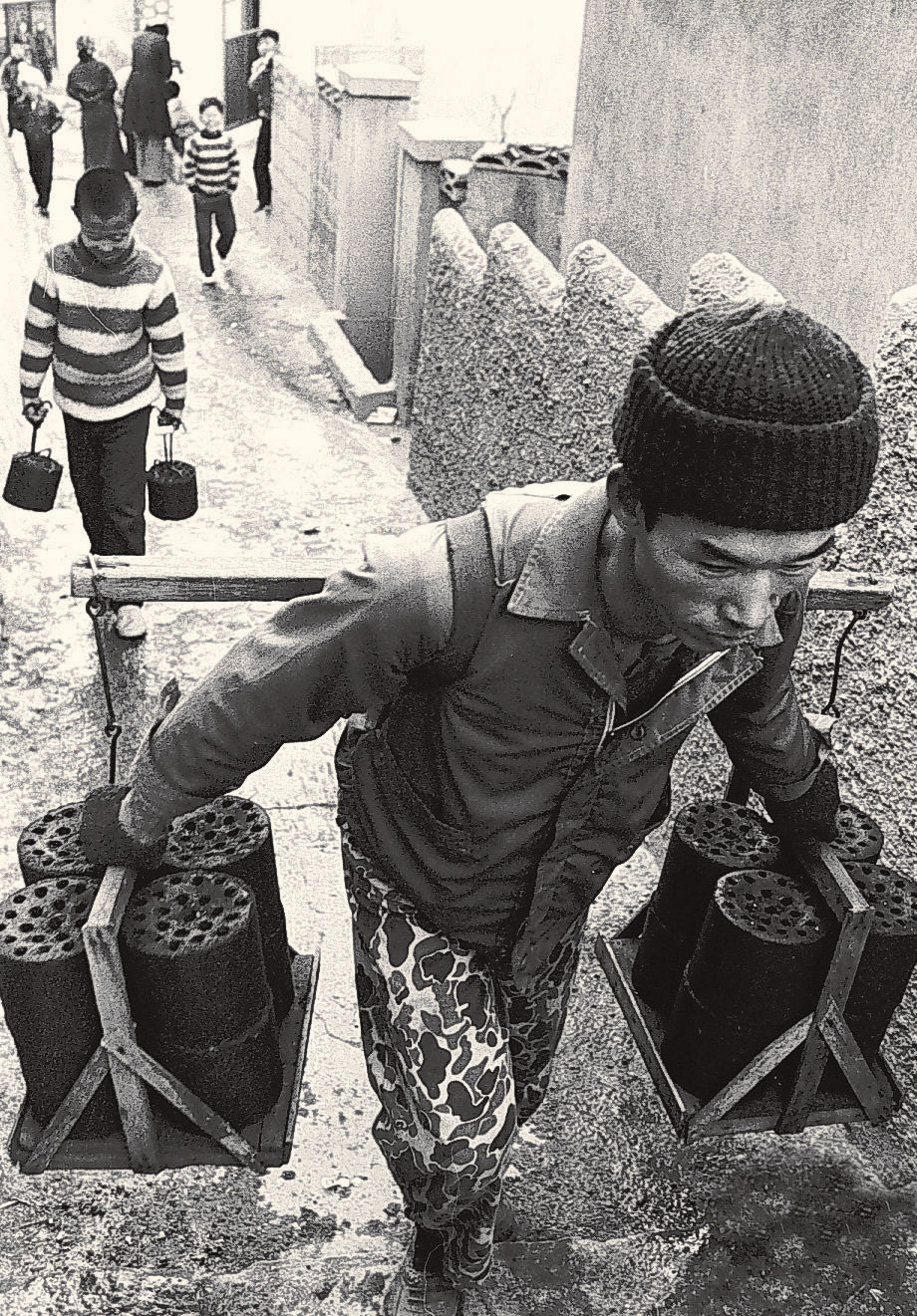

In those days, holed coal briquettes were used for heating and cooking in the cities. On the threshold of winter, it was common for most households to stock their storeroom with high stacks of briquettes. But no matter how many briquettes a customer might order, factories would not deliver them to private homes, leaving buyers no choice but to haul the briquettes in rented handcarts. As demand grew, briquette merchants started providing door-to-door delivery for a fee in the 1970s. Meanwhile, for vendors who had no means of heating in winter, briquette brazier rental services appeared. In the two major markets in Seoul, Namdaemun (South Gate) and Dongdaemun (East Gate) markets, a flock of deliverymen could be seen as early as 5 a.m. on standby with burning briquettes in portable braziers, waiting for orders. To the cost of the briquettes they added a small service fee, and by delivering 200 or so braziers per day they were able to make ends meet.

Unlike older generations, digital natives born after 1980 effortlessly adapted to the latest technologies, and in no time, advanced delivery services became a distinctive feature of Korean society.

The smartphone generation deserves kudos for the nation’s thriving delivery industry today.

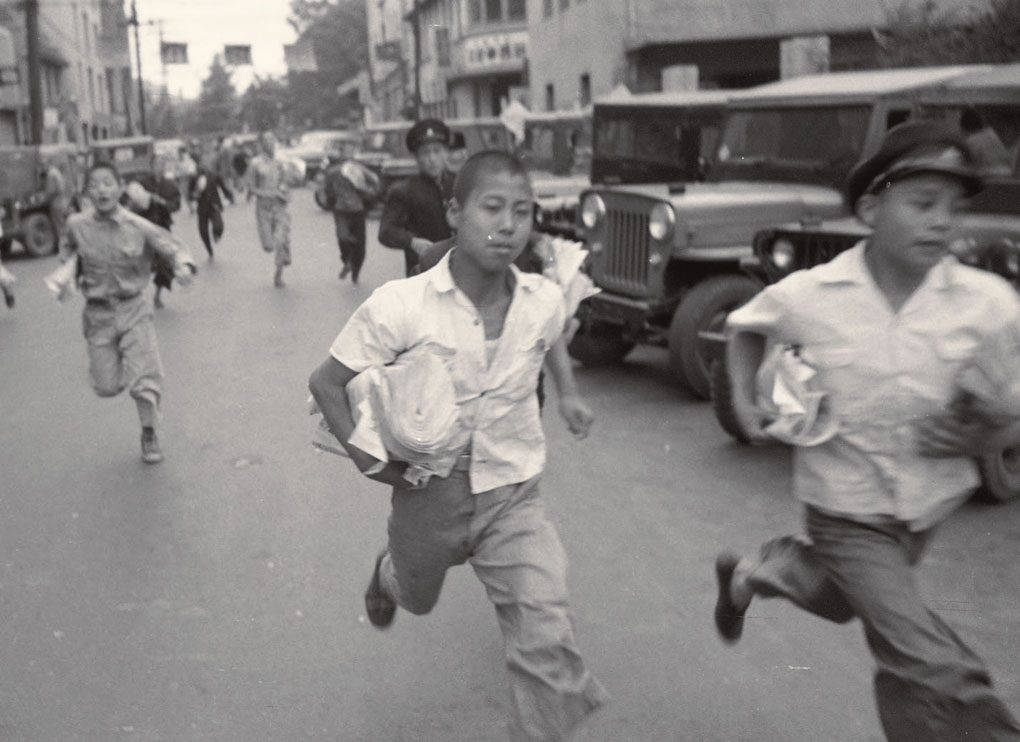

“Another Hopeful Day” (provisional title), a 1960 photograph by Limb Eung-sik, captures young boys running to deliver newspapers in Myeong-dong, Seoul. It was common for children of poorer families to deliver newspapers to earn tuition and pocket money. © Lim Sang-cheol

“Ikseon-dong,” a 1993 photograph by Han Jeong-sik, shows a Chinese food deliveryman riding a bicycle through the alleys of a residential area in central Seoul, holding a large tin box in one hand. Chinese restaurants started to provide delivery service in the 1960s. © Han Jeong-sik

A man delivers coal briquettes using a shoulder pole in a hillside shantytown in Seoul in this photo dating back to the early 1970s. The holed briquettes were widely used for heating and cooking from the post-Korean War era to the 1990s. © NewsBank

Motorcycles and Smartphone Apps

Chinese food started to be delivered widely in the 1960s and remained the most popular delivery food for a long time. Bicycles were still almost the only option available for transporting the orders. Toward the end of the 1970s, when the Korean government’s immigration policy made it harder for Chinese residents to enter Korean universities, they moved to Taiwan in great numbers. As a result, many Korean deliverymen who had worked for Chinese restaurants started their own businesses. Just then, demand for Chinese food delivery surged as huge apartment complexes went up in big cities, creating densely populated residential areas.

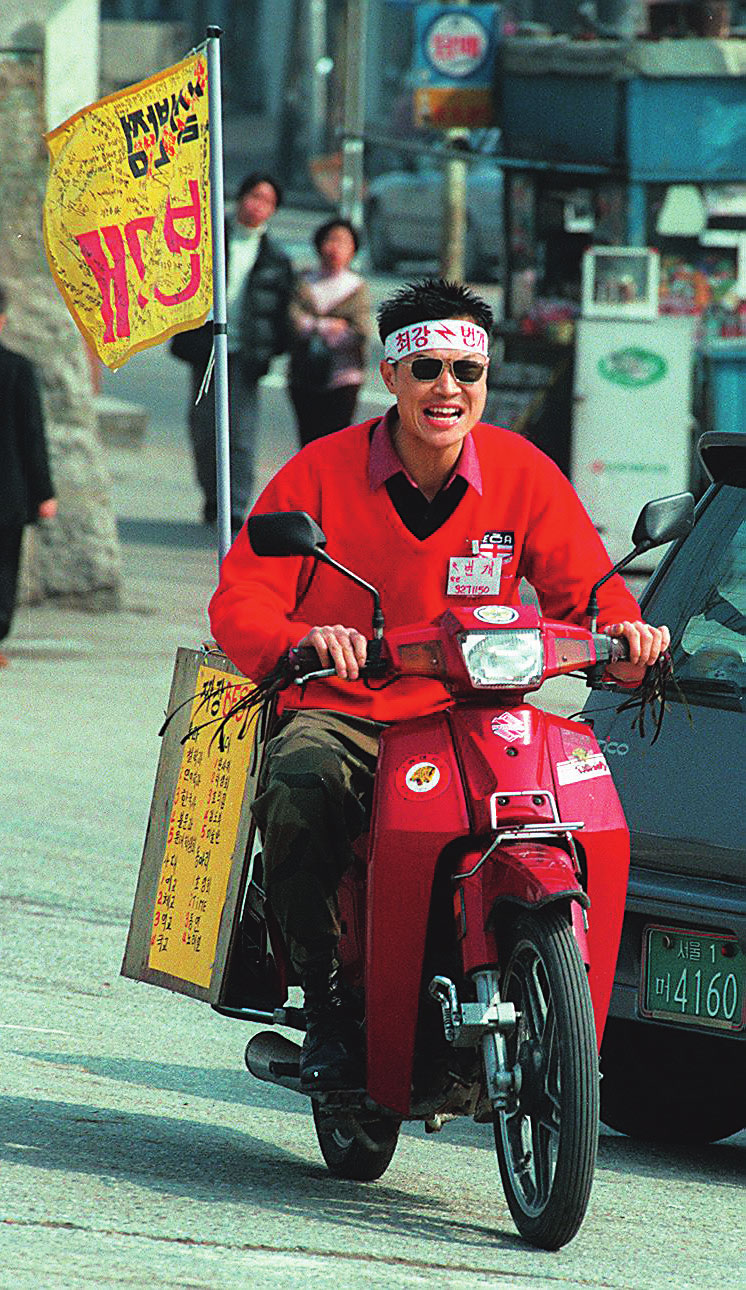

In the 1980s, an increasing number of consumers became capable of affording delivery fees, giving a boost to the industry. In 1982, an economic newspaper counted delivery service as a business with good prospects. On-demand delivery became more widespread in the run-up to the 1988 Seoul Olympics, when American-style fast food chains opened in the city. A new urban scene unfolded: young people riding motorcycles to deliver pizza, a food hitherto unknown to most Koreans. As motorcycles proved to be excellent in terms of speed and efficiency, Chinese restaurants and traditional markets also opted to use them in place of bicycles or walking.

Delivery in its current form, based on door-to-door parcel service, emerged as a promising business model in the 1990s, with the introduction of the Japanese parcel delivery system. At first, Koreans were rather reluctant to adopt the service, considering the separate delivery charge unacceptable. But they soon came to appreciate the convenience of receiving their purchases at home in return for a small fee. Subsequently, parcel delivery services proliferated, deriving further impetus from the appearance of mobile apps in 2010. Unlike older generations, digital natives born after 1980 effortlessly adapted to the latest technologies, and in no time, advanced delivery services became a distinctive feature of Korean society. The smartphone generation deserves kudos for the nation’s thriving delivery industry today.

Working for a Chinese restaurant near Korea University in Seoul in the late 1990s, this deliveryman known by the name of Cho Tae-hun was a neighborhood celebrity for his decorated motorcycle and “lightning” speed. He became famous nationwide after appearing on television. © NewsBank

A woman working for a restaurant in Namdaemun Market in Seoul carries on her head stacked trays of food for merchants who can’t leave their stores to eat. © Seoul Metropolitan Government; Photo by Mun Deok-gwan