Rev. Pang In-sung tries to advance unification through humanitarian assistance, defying ups and downs in inter-Korean relations. He urges South Korean churches to take an interest in giving North Koreans substantial help to improve their livelihood before regarding them as evangelization targets.

Every winter Rev. Pang In-sung leaves for the frigid northernmost edge of North Korea. Sub-zero temperatures are the norm in the border region, where they say “winds are powerful enough to lift cows.”

The philanthropic pastor’s destination is the Rason Special Economic Zone, a slice of North Hamgyong Province, which is wedged between China, Russia and the East Sea. The purpose of his annual visit is to deliver humanitarian aid, a product of his roles as senior pastor of the Open Together Church in Seoul and president of Hananuri, an aid organization affiliated with his church. The recipients are those who are most vulnerable to the threat of frostbite from a brutal winter.

Mufflers and Microfinance

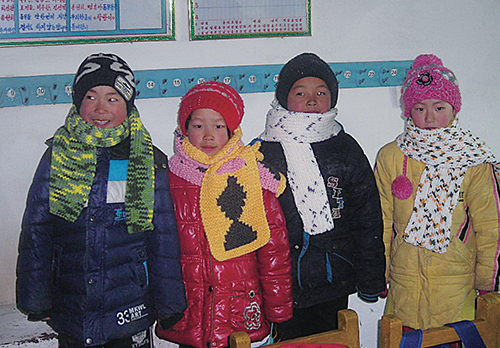

“In the biting winds, we make a round of kindergartens, daycare centers and orphanages, delivering a truckload of about 3,000 mufflers. The children’s faces brighten up when they receive the mufflers,” Pang says. “North Korean children are exposed to winter chill with little warm clothing to protect them, when heating fuel is in very short supply. Mufflers are the best gifts for them in winter. I think those 1-meter-long mufflers connect people in the two Koreas.”

Hananuri (literally, “one world”) also provides financial support in Ryongpyong, a farming village in the Rason area. It runs a communal fund to help the villagers buy farm equipment and supplies to promote self-reliance. It is modeled after the microcredit program of the Grameen Bank founded by Muhammad Yunus, a Bangladeshi social entrepreneur, economist and civil society leader, who received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006.

Hananuri was launched in 2007 with the goal of making preparations for national reunification based on three aspects of support programs: practical activities, research and education for building peace on the Korean peninsula. Its newly opened think tank, the Northeast Asia Research Institute, is tasked with creating a win-win development model for Northeast Asia. Currently, it is studying Ryongpyong as a possible prototype.

Through Hananuri as well as his Open Together Church, a small church with only some 100 members, Rev. Pang hopes to convince South Korea’s megachurches to reconsider their post-unification plans. “South Korean churches are mostly thinking of opening churches in the North, once the nation becomes reunified. But they should pay attention first to how to provide real help to North Koreans.”

Children at a daycare center in the Rason Special Economic Zone, North Korea, wear mufflers knitted by volunteers in South Korea. Mufflers are timely gifts during the icy winter weather in North Korea, where heating fuel is in short supply..

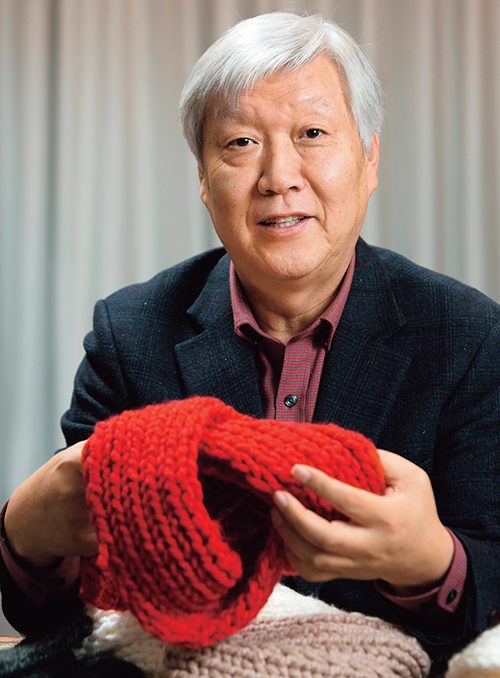

Young volunteers knit mufflers at the office of Hananuri, a nongovernmental aid organization, in Jung District, Seoul. They come every fourth Saturday of the month. Those who cannot come receive knitting materials at their homes and send the finished mufflers to the office.

Volunteer Knitters

In 2011, a Hananuri staffer suggested giving mufflers as gifts to North Koreans. Inter-Korean relations were deadlocked at the time, with exchange programs almost completely stalled. Pang felt that private sector exchanges should be maintained, regardless of the state of relations between the governments. The idea of knitting mufflers struck him as fresh and original. “It was a great idea. Even North Korean officials marveled at how we conceived of such an idea,” Pang says.

Most of the mufflers distributed through his “Mufflers Connect Both Koreas” campaign are knitted by South Korean middle and high school students. By participating in the campaign, the students earn school credits for volunteer community service. On the fourth Saturday of every month, they gather at the Hananuri office in Seoul’s Jung District to knit together. Those who cannot come receive knitting materials at their homes and send the finished mufflers to the office. The knitting materials are funded by donations.

Children and teachers at North Korean kindergartens and daycare centers are particularly touched when they hear that the mufflers were knitted by South Korean students, probably because they feel they have received truly warm gifts. This is why Pang adheres to having mufflers voluntarily hand-knitted one by one, although he knows it would be far simpler to buy and send them to the North.

Employees of Samsung Display and other Korean companies have also become involved in the campaign, and proposals to participate come from the United States and Canada, among other countries. “Some 2,000 to 3,000 people at home and abroad participate every year,” Pang says.

Communal Fund for Self-Reliance

Hananuri’s activity in Ryongpyong began in 2009, when it provided assistance to daycare centers in Chongjin, also in North Hamgyong Province, and orphanages in nearby Ryanggang Province.

In 2017, Hananuri began a 10-year project to help Ryongpyong become more self-sufficient in food supply, childcare, housing, education, medical service, energy and self-administration. The village fund, part of the project, extended a loan equivalent to some 33 million South Korean won (approximately US$30,000) to the village’s 48 households. With the money they purchased seeds, fertilizer and farm equipment for the 615,000 square meters (152 acres) of land that they tend.

The success or failure of such self-reliance projects depends on whether the villagers can repay their loan. The village’s 2017 performance report helped mollify any concerns. Rice and corn output increased by about 60 tons each, compared to 2016, and each household’s consumption of rice and noodles increased by about 10 kilograms year-on-year. The first repayment was made on July 17, 2018.

“Ryongpyong is a diffusion model that can be applied to any other place in the North,” Pang says. He plans to reinvest the repayment in another village in Rason.

“North Korean children are exposed to winter chill with little warm clothing to protect them, when heating fuel is in very short supply. Mufflers are the best gifts for them in winter. I think those 1-meter-long mufflers connect people in the two Koreas.”

A chicken farm in Ryongpyong Village in the Rason Special Economic Zone, North Korea, in 2018. Hananuri is helping the village’s 48 households become self-reliant through a funding project.

Preparing for Post-Unification Era

Hananuri intends to open a representative office in Rason for on-site management of its aid projects. The office will also reinvest profits and serve as a communication channel for South Korean corporations. Over the mid- and long-term, the office will conduct research on tourism, foreign language education, transportation, fish farming, underground resources development and smart city programs as well as urban planning and land development.

While undertaking the Ryongpyong project, Rev. Pang learned that most villagers had heavy debt loads. He also came to know that loans with an interest rate of 10 to 30 percent are commonplace in the North. Many North Koreans do not trust banks, because they suffered substantial losses in the 2009 currency reform, which forced everyone to obtain new banknotes while limiting the swappable amount of the suddenly obsolete old currency.

Loan sharks have filled the void created by the distrust of banks and the amount of household loans is raising alarm. To help relieve the pressure, Pang is preparing to let the communal fund offer an interest-free loan of up to an equivalent of 85,000 South Korean won to individual households. The average monthly cost of living per household amounts to some 50,000 South Korean won.

Hananuri has another think tank devoted to the study of land use, namely the Institute of Land and Liberty. Research at the institute is focused on a jubilee cycle of economy, referring to an early biblical tradition in which land, property and slaves would be returned to their owners in the 50th year. The research concerns how land and property should be handled in the North after unification and what alternative economy could apply to both Koreas.

“I believe that we need a new alternative economic structure for the unified peninsula, transcending the current systems of both Koreas,” Pang says. “The new alternative structure will have to envision genuine peace, following the biblical tradition of the Jubilee.”

During the liberal administration of President Roh Moo-hyun (2003-2008), Hananuri sponsored joint exhibitions of South and North Korean artists and provided youths from both Koreas with an opportunity to plant trees together. In 2007, it envisioned 500 youths from both sides crossing the Demilitarized Zone on bicycles. But after the conservative Lee Myung-bak administration took over the following year, the cross-border bike ride had to be abruptly cancelled.

“The Unification Ministry and potential sponsors, as well as the North Korean authorities, took a great interest in the event,” Pang says. “But we couldn’t go ahead because inter-Korean relations chilled. We had already reached an agreement with the North’s National Economic Cooperation Federation and we were just about to start it. I want to push for the event again if another chance comes sometime in the future.”

The hostile political environment is not the only obstacle to Pang’s aid projects. Hananuri’s activities are not properly understood even by South Korean churches. Some compare his projects to “shoveling sand against the tide.” But Pang’s stress on grassroots support is unwavering.

“More chaos will result in the North if South Korea’s megachurches and various Christian denominations and organizations compete only to open churches and expand their influence there,” he says. “I hope South Korean churches won’t regard North Koreans merely as targets of evangelization, but will love them first and then think seriously of ways for people of both Koreas to live together peacefully.”

Rev. Pang In-sung is shaping a win-win development model for post-unification Korea in addition to providing substantial assistance to North Koreans through Hananuri, a nongovernmental aid organization founded in 2007.

Efforts for Church Reform

Pang is a third-generation pastor in his family. His grandfather, Rev. Pang Gye-sung, aroused his interest in North Korea and the unification of the divided peninsula. “I was more and more interested in unification and peace, as I believed that loving North Koreans is the essence of the gospel, transcending the tragedy of my own family,” he says.

Rev. Pang Gye-sung was a pastor from Cholsan, North Pyongan Province. He was imprisoned for refusing to pay respects at Shinto shrines during the Japanese occupation of Korea. After the national liberation in 1945, communists killed him for refusing to put up a North Korean national flag at his church and join the North’s Christian federation.

Pang In-sung studied theology at King’s College London and the University of Oxford’s Faculty of Theology. He was ordained as a minister at the International Presbyterian Church in the United Kingdom and worked as a curate at a Korean church in Kings Cross, London, and as senior pastor at another Korean church in Oxford.

After returning to South Korea in 1996, he took charge of the Seongteo Church, which was built in Seoul by Protestants who were incarcerated for refusing to pay respects at Shinto shrines during the colonial period. He has only one kidney because he donated the other to a sick member of the church. It was a decision based on his conviction of “practicing what you preach.” In 2014, Pang staged a 40-day hunger protest at Gwanghwamun Square in downtown Seoul, seeking justice for the victims of the Sewol Ferry disaster that year, most of them high school students.

Pang also is known for his advocacy for small church. In cooperation with the Solidarity for Church Reform in Korea, he is conducting a Protestant reform movement that seeks an end to hereditary succession of church administration and leadership.